Top Aging Scientist Critiques Bryan Johnson’s Attempt to Live Longer Through Gene Therapy

Aging researcher Dr. Matt Kaeberlein quips that there is a lack of evidence for safety and efficacy regarding a gene therapy Bryan Johnson is using for lifespan extension purposes.

Highlights

- The gene therapy increases the activation of a gene that produces a protein called follistatin, which purportedly boosts muscle growth and increases insulin sensitivity.

- Bryan Johnson found that follistatin gene therapy increased his lean muscle mass and lowered his pace of aging as measured with biological age—an age assessment reflecting cell and tissue function.

- Despite Bryan Johnson’s positive findings, Dr. Kaeberlein says there is a lack of evidence for the safety of follistatin gene therapy, especially since the long-term risks are largely unknown.

Bryan Johnson is an American venture capitalist who is well-known for his quest to maximize lifespan, allotting some $2 million yearly toward supplements and therapies related to this endeavor. Interestingly, in 2023, he traveled to the Honduran island of Próspera to undergo a controversial gene therapy that can potentially extend human lifespan. He went to Próspera for one key reason—it is illegal in the US to undergo this gene therapy procedure since it has not received FDA approval. In Próspera, companies like Minicircle, who provided Johnson with the gene therapy, steer clear of FDA oversight and regulation, and since the Honduran government gives lax regulatory oversight, these companies can provide their questionable aging interventions there.

Dr. Matt Kaeberlein, a well-renowned aging researcher from the University of Washington, critiqued Bryan Johnson’s YouTube video that described how he underwent this gene therapy. In an Optispan podcast video, Dr. Kaeberlein, with Optispan’s co-host, Nick Arapis, describes the science behind follistatin gene therapy, saying that it increases levels of the follistatin protein. Research has shown that follistatin suppresses a muscle growth-inhibiting protein called myostatin. In doing so, increasing follistatin boosts muscle growth in mice and extends their lifespan. Since human trials that investigate boosting follistatin are lacking, it appears that Bryan Johnson is taking a leap of faith with the hope that increasing this protein with gene therapy will not only drive muscle growth but also extend his lifespan.

Dr. Kaeberlein has a few issues with this approach. First of all, he questions the ethics of people who work outside of the confines of FDA regulation. This leads him to neither trust the people who run the company Minicircle nor the quality of the therapy they are selling. Furthermore, Dr. Kaeberlein says that there is a lack of evidence for the long-term safety and efficacy of follistatin gene therapy. This makes him believe that eventually, someone undergoing controversial interventions like follistatin gene therapy in Próspera will die.

Gene Therapy Based on a Circular Strand of DNA

Dr. Kaeberlein begins by describing the technology that Minicircle is using. In that regard, the company uses a circular piece of DNA (known as a plasmid) derived from bacteria that is not supposed to integrate into DNA. Cells can use the plasmid, which contains genetic information, to increase the abundance of follistatin proteins. Interestingly, this gene therapy currently costs a whopping $25,000.

Dr. Kaeberlein then reviews Bryan Johnson’s claim that the gene therapy has a built-in kill switch that turns the gene therapy off. According to Bryan Johnson, you can avoid risks like cancer by turning off this gene therapy through administering the antibiotic tetracycline.

Dr. Kaeberlein says that this claim provides a false sense of security, because once you get cancer, whether you turn the gene therapy off or not, you still have cancer. This is not to say that there may not be some advantage to turning the gene therapy off, according to Dr. Kaeberlein. For example, if someone got cancer with the gene therapy, turning off the gene therapy may help prevent making the cancer worse.

Not only that but the mechanism to turn the gene therapy off is not always 100% effective. In that regard, he says that some of the methods for turning gene therapies off are somewhat “leaky” in the sense that you can turn the gene therapy down with tetracycline but not completely stop gene activity induced from the therapy.

A Purported Dramatic Lowering of Biological Age

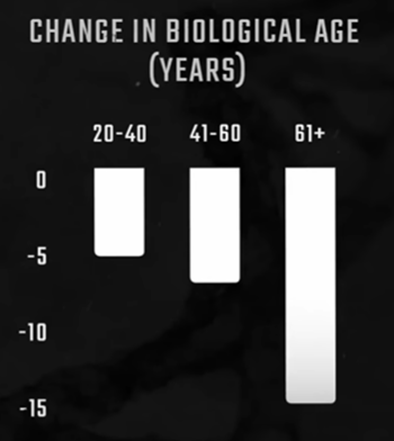

Next, Dr. Kaeberlein goes over a graph that Bryan Johnson presents showing that follistatin gene therapy reduces biological age. According to the data, the therapy reduces biological age by about five years in those aged 20 to 40 years, about seven years in 41- to 60-year olds, and almost 15 years in people over the age of 61.

One issue that Dr. Kaeberlein has with this data is that the measurement of biological age used was based on the analysis of DNA chemical modifications (an evaluation known as epigenetic age). According to Dr. Kaeberlein, epigenetic age is only one metric of many that can be used to analyze biological age, and he finds this measurement insufficient.

“Science should not be done on YouTube. There is absolutely no reason to trust these people. They are trying to sell you something,” says Dr. Kaeberlein.

Bryan Johnson Showed Improved Body Composition

After going over the claims pertaining to lowering biological age, Dr. Kaeberlein reviews some of Bryan Johnson’s personal data after receiving follistatin gene therapy. Interestingly, about 16 days after the therapy, Bryan Johnson showed about a 160% increase in circulating follistatin. Dr. Kaeberlein says that this finding suggests that the therapy is effective at increasing follistatin and that this would likely increase muscle synthesis. He adds that there is some evidence that transiently, not permanently, increasing follistatin may induce an improved body composition—less fat and more muscle.

In line with the effects that researchers believe follistatin has on increasing muscle and reducing fat, Bryan Johnson revealed that six months after the follistatin gene therapy, his muscle mass increased 7%, and his body weight increased 5%. This finding suggests an increase in lean muscle. Dr. Kaeberlein says that this is probably what he would expect with follistatin gene therapy and thinks similar effects could be seen with use of anabolic steroids.

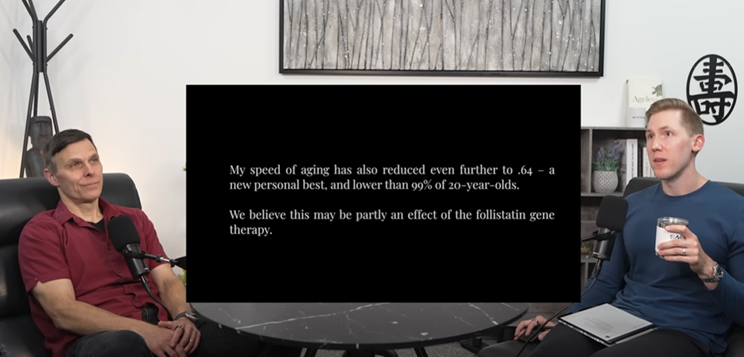

Moreover, Bryan Johnson relayed that after undergoing follistatin gene therapy, his pace of aging was reduced to 0.64, well below the typical speed of aging of about 1.0. Dr. Kaeberlein retorts that Bryan Johnson is referring to the DunedinPACE aging metric that evaluates biological age. He adds that this metric is not as convincing as the positive body composition data that Johnson also shared.

Insufficient Data for an Adequate Risk-Reward Analysis

Dr. Kaeberlein adds that there is virtually no ability to do a risk-reward analysis of this procedure, because so few people have undergone follistatin gene therapy. Moreover, of the few who have had follistatin gene therapy, no one has likely undergone treatment for more than two years. In that regard, there is no existing insight related to safety and efficacy. Since we know nothing about the risk profile of follistatin gene therapy, there is no way to analyze what the unanticipated adverse outcomes of increasing follistatin might be.

In closing, Dr. Kaeberlein mentions that some of the genetic information from the plasmids used to deliver follistatin gene therapy might integrate into DNA with a very low frequency. He says that because of this, there is some risk of permanently altering genes contained in DNA. There is a pretty good chance that these integration events will not have a major effect, but there is some chance that they might. For this reason, he thinks we need more data on the long-term risks associated with this therapy.

“It’s almost inevitable, somebody’s going to die,” says Dr. Kaeberlein. “And maybe somebody’s died already and we just haven’t heard about it. That’s part of the uncertainty of these offshore clinics.”

Because there is no reporting obligation for any of these offshore clinics, there needs to be a rational risk-reward analysis before undergoing this therapy, according to Dr. Kaeberlein. Because this is not possible, Dr. Kaeberlein says undergoing follistatin gene therapy just does not add up.