Exploring the Longevity Paradox: Can Obesity Increase Lifespan or Is BMI an Inadequate Measure?

There is a continuous scientific debate over whether obesity can lower the risk of mortality for specific individuals.

Highlights:

- Specific obese individuals have lower mortality rates than non-obese individuals.

- Body mass index (BMI) is a poor indicator of health, whereas abdominal obesity more accurately predicts mortality risk.

- Exercise can lower the chances of premature death from obesity.

Considering that obesity is generally thought to lead to a shorter life, the obesity paradox arises from studies suggesting that obesity promotes a longer life. Indeed, several studies have shown that obesity is associated with a reduced risk of mortality, especially in the elderly. For this reason, scientists have debated over whether obesity should be treated as a disease, particularly in old age, as it may protect against aging. However, the validity of these studies has been called into question because of how obesity is traditionally measured.

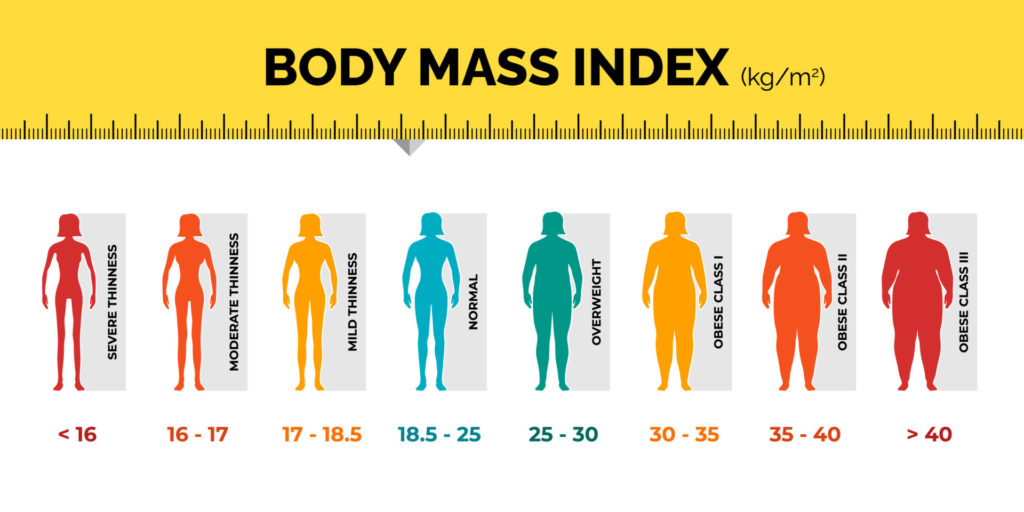

Body Mass Index (BMI)

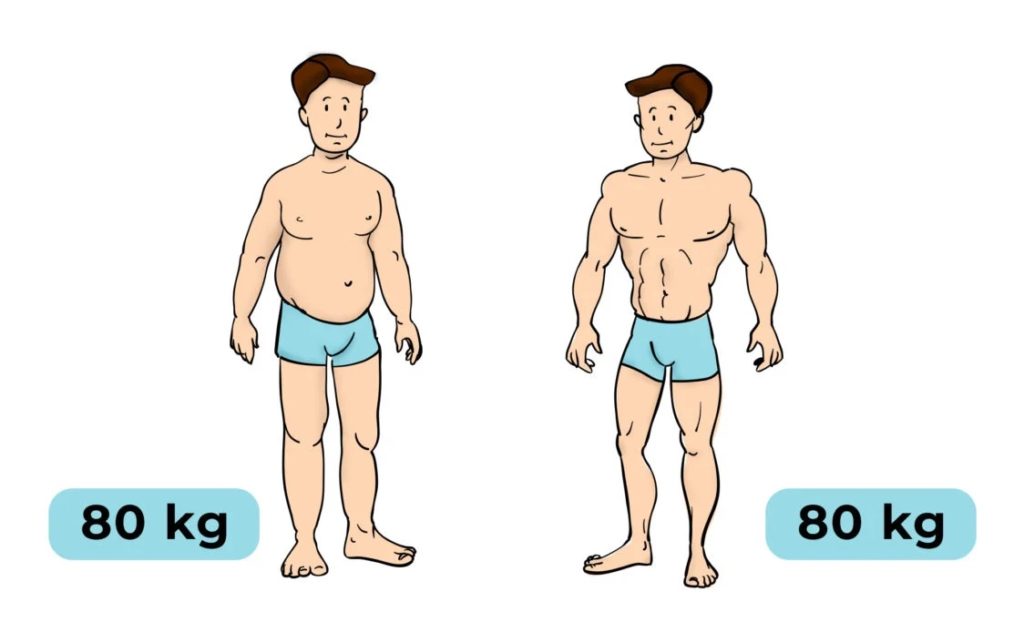

In studies like the ones in question, participants are compared based on their body mass index (BMI) — weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. Participants with a BMI higher than 30 kg/m2 are classified as obese — having excess body fat. However, our bodies are composed not only of fat, but also of muscle, bone, and other tissues. Some of these tissues, like muscle and bone, weigh more than fat. As such, bodybuilders with very little body fat and a lot of muscle are classified as obese.

On the other hand, someone with reduced muscle or bone mass can have a normal BMI. This is important because reduced muscle mass is a key characteristic of a disease called sarcopenia, which is associated with a higher risk of mortality. Osteoporosis, a disease characterized by reduced bone mass and density, is also associated with an increased risk for mortality. Both diseases can go undiagnosed and neither can be detected via BMI.

Additionally, BMI does not take into account the distribution of fat, meaning that individuals with a normal BMI can have high levels of abdominal fat. High abdominal fat, which can be assessed by waist circumference, may be more lethal than fat distributed elsewhere (e.g. thighs and hips). For example, one study found that mortality rates were substantially higher in normal-weight individuals with high levels of abdominal fat, as compared to those with less abdominal fat.

(Image: gymbeam.com) “Skinny Fat.” Normal weight obesity, colloquially “skinny fat,” is defined by increased body fat with a normal BMI. The cut-off body fat percentage for this condition is not yet agreed upon, but has been reported to be over 20-25% in males and over 33-35% in females.

Suffice it to say, BMI can accurately estimate obesity in the average person, as most individuals are not bodybuilders. However, it cannot be assumed that individuals with a normal BMI are healthy, especially in elderly individuals who may have reduced muscle and bone mass. Thus, there is an inherent flaw in comparing the mortality rates of people based on their BMI alone.

When Fat is Fine

The obesity paradox applies primarily to specific individuals. Reports show that obesity is associated with lower mortality in individuals with conditions like heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, and diabetes or who have undergone procedures like hemodialysis or surgery. In individuals without these conditions, who have not undergone these procedures, higher BMI predicts an increased risk of mortality. Additionally, the obesity paradox disappears when not using BMI as a measurement of obesity and abdominal fat, particularly visceral fat (fat surrounding the organs), is the main culprit for increased mortality rates.

However, a subset of obese individuals who are metabolically healthy have been documented. One study found that these metabolically healthy obese individuals were more physically fit than non-metabolically healthy obese individuals. In line with this, another study showed that unfit obese individuals are doubly at risk of heart disease than fit obese individuals. Furthermore, when compared to fit obese people, unfit lean individuals are at higher risk for metabolic disease.

Thus, obesity appears to be less harmful in individuals who exercise. Exercise has many beneficial effects, including maintenance of muscle and bone mass, especially in the case of resistance exercise. Moreover, exercise may counteract the metabolic deficits associated with obesity by improving blood pressure and reducing inflammation while reducing visceral fat and combating insulin resistance. Hence, there is such a thing as being fit and fat.

Losing Weight Before Old Age to Live Longer

In 2017, a meta-analysis of 54 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that losing weight via diet with or without exercise reduces the risk of premature death in obese adults. This study suggests that for the general obese population losing weight can lead to a longer lifespan.

However, in the case of older adults, a 2023 analysis of a RCT showed that losing weight is associated with an increase in all-cause mortality. The authors note that they were not able to determine if the weight loss was voluntary or involuntary. Involuntary weight loss can imply serious underlying health conditions like cancer. It is also possible that diseases like sarcopenia and osteoporosis were involved, as weight loss can lead to further muscle and bone loss, exacerbating these diseases. Furthermore, the authors had no record of the participant’s diet and physical activity levels.

Overall, it would seem that obese individuals below the age of 60 who do not have underlying conditions may benefit from weight loss, whereas losing weight may not be beneficial for those with conditions like cancer, sarcopenia, or osteoporosis.