Taking Probiotics Could Have Similar Effects as Fecal Matter Transplant in Treating Aging

Older mice given fecal microbiota transplantations from younger mice had reduced age-related disorders, such as sugar intolerance and gut barrier dysfunction, due to increased Akkermansia muciniphila (a type of bacteria) and its metabolite, acetic acid.

Highlights:

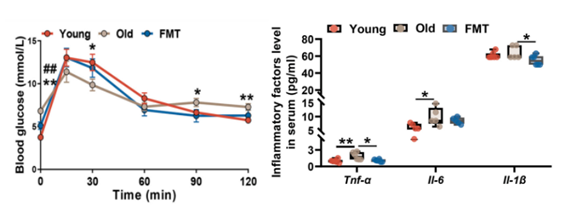

- Old mice treated with fecal microbiota transplantations (FMT) from mice had improved sugar tolerance, inflammation, and intestinal barrier.

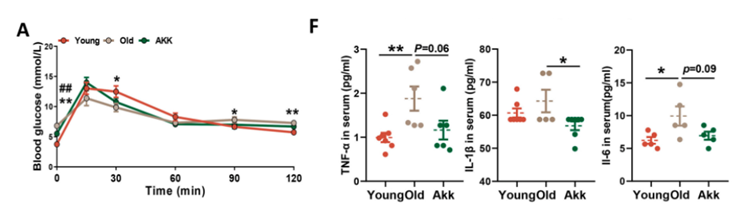

- Treating old mice with A.muciniphila – a bacteria which increases with FMT and is normally decreased in old mice – had results similar to FMTfrom young mice.

- Both A.muciniphila and FMT increase acetic acid in the intestines and treating mice with acetic acid yields similar results to FMT and A.muciniphila treatment.

Multiple studies have shown how interconnected the gut microbiome – bacteria that populate our intestines – and age-related disorders are. A recent study shows that supplementing with specific bacteria and its by-products can turn back the clock on aging.

The study, out of China and published in Pharmacological Research, focuses on aged mice. The old mice were treated with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) – transferring of bacteria from feces – from young mice, which altered their gut microbiota, leading to improved age-related disorders across a range of body systems, including improved liver damage, sugar tolerance, and the intestinal barrier. The scientists found that the FMT from the young mice led to an increase in A.muciniphila, which prior to the FMT, was nearly undetectable in the old mice. A new cohort of mice was treated with just A.muciniphila, and an outcome similar to FMT treatment was seen. The researchers found that acetic acid – which plays a role in fat and carbohydrate metabolism and is a byproduct of A.muciniphila metabolism – was elevated in both FMT- and A.muciniphila-treated mice. Acetic acid treatment also led to beneficial outcomes in aged mice.

“This study highlights the potential of improving aging-related disorders by remodeling gut microbiota, in particular with A.muciniphila and acetic acid,” the investigators wrote.

Young Gut Bacteria Reverse Age-related Gut Diseases

Ma and colleagues treated 18-month-old mice (approximately 56 in human years) with FMT from 4-week-old mice (approximately 14 in human years) in order to restructure the gut bacteria of the aged mice. FMT has previously been shown to help alleviate certain bacterial infections (C. Diff, in particular) by changing the recipient’s gut microbiome. In this study, the researchers found that the rate at which sugar was cleared from the bloodstream (glucose tolerance) was improved in the old mice following FMT. Furthermore, markers of liver damage and inflammation were decreased, while antioxidant proteins were increased in the aged mice. The proteins involved in maintaining the intestinal barrier – which has been shown to affect a large range of issues when it is not functional – were also increased following FMT.

FMT also led to the treated old mice having a gut bacteria make-up similar to the young mice, with more diversity than normally seen in aged mice. FMT increased the Akkermansiaceae bacteria family in old mice, particularly A.muciniphila – the most abundant member of the Akkermansiaceae family – suggesting that FMT can partially reverse gut dysbiosis, or gut bacteria imbalance associated with disease.

Young Gut Bacteria and its Metabolites Recapitulate Effects of FMT

Due to the dramatic increase in A.muciniphila following FMT, Ma and colleagues tested whether supplementing mice with live A.muciniphila yielded similar effects. A.muciniphila treatment also improved glucose tolerance, liver damage markers, antioxidant proteins, and inflammatory markers. The intestinal barrier function was also improved with A.muciniphila treatment, suggesting that live A.muciniphila alone can recapitulate the effects of FMT on old mice.

A.muciniphila is known to generate short-chain fatty acids through its metabolism, which in turn have been reported to help mediate the intestinal barrier and immune regulation. Both FMT and A.muciniphila helped to increase acetic acid – one of the major short-chain fatty acids – in the intestines of old mice, suggesting that the beneficial results may be due to increased acetic acid, which normally decreases with age. The scientists treated old mice with sodium acetate – the salt form of acetic acid – to investigate whether the benefits were due to increased acetic acid. They found that acetic acid supplementation led to improved antioxidant processes, reduced inflammatory markers, and improved intestinal barrier function, suggesting that the increased acetic acid was responsible for the benefits of both FMT and A.muciniphila treatments.

Young Bacteria for Gut Health

Ma and colleagues show here that transplanting young bacteria into old mice leads to improved aging-related concerns, and that similar results are seen when the bacteria seen in young mice, especially A.muciniphila, are introduced into old mice. Additionally, metabolites of the bacteria seen in young mice, specifically acetic acid, also led to similar results.

Previous research has shown that gut bacteria transfers from young mice can lead to rejuvenated muscle and skin and decreased age-related inflammation. Meanwhile, this study shows that these bacteria transfers can also lead to rejuvenated intestines and liver. All these studies serve to pave the way for using FMTs for anti-aging purposes. However, Ma and colleagues point out that FMTs are not without controversy, and even using A.muciniphila as a probiotic can lead to Parkinson’s concerns. Thus, they investigated acetic acid supplementation and found that it too can lead to reversing age-related concerns, and acetic acid has been previously shown to lead to anti-aging effects in the skeletal muscles in rats.

Human studies, with long-term follow-up, are needed before proclaiming FMT, A.muciniphila probiotics, or acetic acid supplementation as valid anti-aging therapies for maintaining the intestinal barrier and healing the liver, but acetic acid supplements are already being touted as being able to reduce blood pressure, blood sugar, inflammation, and help support weight loss, as well as helping to maintain helpful bacteria. As always, speak to your healthcare provider before stopping or starting any new medications or supplements.

Model: Male C57BL/6 J mice; 10-month-old

Dosage: Fresh feces pellets (80–110 mg) were collected from young donor mice and placed into autoclaved tubes and homogenized in 1 mL of sterilized Phosphate-Buffered Saline, PBS (135 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, PH7.4)