Study Shows NMN Delays Stroke in Rodents

Rats with increased blood pressure and stroke predisposition have decreased NAD+ levels

Highlights

· Defective cell recycling processes favor hypertension-related spontaneous stroke in rats fed high-salt diets.

· NMN treatment reverses these processes to protect against stroke occurrence in these rodents.

Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and disability and has an array of risk factors including our genetic makeup and lifestyles that increase blood pressure, or what’s called hypertension in the medical field. To date, there are no effective treatments for this disease, so figuring out how hypertension predisposes people to stroke may improve its preventive and therapeutic strategies. Although there have been hints for the role of the cell’s recycling processes known as autophagy in the development of hypertension-related stroke, this connection remains unclear.

Forte and colleagues from the Sapienza University of Rome published an article in the journal Autophagy showing that defective autophagy favors hypertension-related spontaneous stroke by promoting dysfunction of the mitochondria, the cell structures responsible for generating energy. The Italian research team fed rats high-salt diets to cause hypertension and increase the risk of stroke and found a reduction of autophagy in the rodent brains.

This impairment in autophagy was linked to mitochondrial dysfunction and depletion of the essential bioenergetic molecule nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+. When the researchers restored NAD+ levels with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), they saw a reactivation of autophagy and reduced stroke development in the stroke-prone rats. These findings suggest that interventions aimed to boost NAD+ levels and activate autophagy may represent novel therapeutic strategies for subjects at higher risk to develop stroke.

Is Autophagy at the Heart of Stroke?

From single-cell organisms to the most complex multicellular ones, autophagy plays a vital role in the removal of damaged cellular components. One type of autophagy called mitophagy is devoted to the clearance of damaged mitochondria, ensuring mitochondrial quality control. Autophagy is usually activated in response to stress to remove dysfunctional mitochondria, which are then substituted with newly formed healthy ones.

Impairment of autophagy leads to the lack of a proper mitochondrial turnover with the resulting development of mitochondrial dysfunction, which can lead to the progression of cardiovascular diseases, including stroke. Mitochondrial dysfunction causes energy depletion, harmful oxygen-containing molecule buildup (oxidative stress), and inflammation, which are all major determinants of brain injury due to lack of blood flow. Along these lines, autophagy inhibition would favor mitochondrial dysfunction and increase the susceptibility to stroke in the presence of risk factors. But the exact role of autophagy in the development of stroke remains unsolved.

NMN Reverses Autophagy Defects and Protects Against Stroke Occurrence

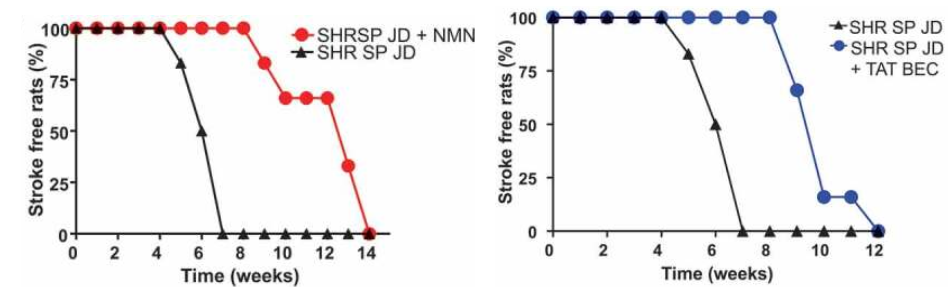

Forte and colleagues tested the link between autophagy impairment and spontaneous stroke development in stroke-prone hypertensive rats, which represents a suitable model for the study of human stroke. This rat model develops spontaneous stroke, with an incidence of 100% after 7 weeks of high sodium and low potassium diet. In this model, the occurrence of stroke is preceded by the development of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in brains and cerebral vasculature, which finally leads to brain edema and stroke.

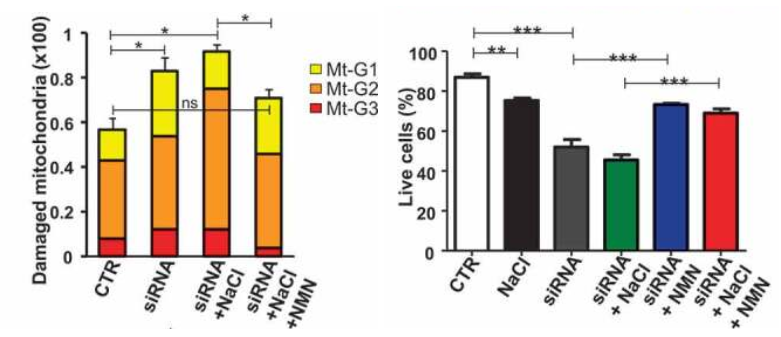

The Italian research team found that autophagy inhibition in these stroke-prone rats in response to high salt dietary feeding is dependent on the dramatic drop of intracellular NAD+ levels in the brain. But when they injected these rodents with the NAD+ precursor NMN (250 mg/kg) daily, Forte and colleagues rescued NAD+ levels in the brain, which was linked to improvements in autophagy, the clearance of damaged mitochondria, and mitochondrial function. They also saw an increase in the survival of blood vessel cells in the brains of rats predisposed to stroke with high salt diets.

Importantly, NMN strongly blunted stroke occurrence in high salt-fed stroke-prone rats. Notably, more than half of the animals receiving NMN survived from stroke until the 12th week as compared to the untreated rats fed with a high salt diet. Forte and colleagues then doubled down on showing that dysfunctional autophagy was at the root of stroke predisposition in the high salt diet fed rats by activating autophagy. Notably, the protective effect of stimulating autophagy in preventing stroke occurred independent of blood pressure levels.

These results clearly indicate that autophagy impairment may contribute to the development of cerebrovascular damage and stroke occurrence. Autophagy reactivation may favor the removal of dysfunctional mitochondria and limit the damage of endothelial and cerebral cells in response to high salt treatment, thereby delaying the onset of brain injury. In conclusion, these findings suggest that interventions aimed to activate autophagy and boost NAD+ levels may represent novel therapeutic strategies for subjects at higher risk to develop stroke.