Stanford Study Suggests Metformin Can Extend Lifespan of Seniors with Delirium and Dementia

Diabetes increases the chances of delirium – a disturbed state of consciousness – and mortality, except with a history of metformin use.

Highlights

- Metformin use reduces the probability of delirium, which increases in prevalence with age in diabetes patients.

- Diabetes patients who take metformin show survival chances comparable to individuals without diabetes.

- In individuals with dementia and delirium, diabetes patients who took metformin have lower mortality risks than patients without diabetes.

The incidence of delirium – a disturbed state of consciousness marked by confusion, disorientation, and hallucinations – is higher in people with dementia. Furthermore, type 2 diabetes increases the risks of dementia. For this reason, researchers have sought to uncover a link between diabetes and delirium. In their quest to uncover this link, researchers have analyzed individuals taking the anti-diabetes drug metformin to find whether it reduces the onset of delirium in diabetic patients.

Published in Aging, Shinozaki and colleagues from Stanford University in California show data suggesting that metformin reduces the probability of delirium in diabetic patients. Moreover, diabetes patients on metformin exhibit improved chances of survival over a three-year period compared to diabetes patients who do not take metformin. What’s more, in individuals with dementia and delirium, diabetic patients who took metformin had lower mortality risks than non-diabetic patients. These findings support further research investigating metformin’s pro-longevity benefits.

“In this report we aimed to investigate the relationship between [type 2 diabetes] and delirium risk with a focus on the influence from metformin,” said Shinozaki and colleagues.

Metformin Reduces Delirium Prevalence and Improves Survival in Diabetes Patients

To examine whether metformin reduces the probability of delirium for diabetes patients, Shinozaki and colleagues analyzed 1,404 subjects. The average age of these individuals was 68.6 years, and among them, 506 had diabetes, with 264 of the diabetes patients having a history of metformin use. The prevalence of delirium in diabetes patients who didn’t use metformin was significantly higher than in those without diabetes. A non-significant statistical trend also suggested that diabetic patients who used metformin had a reduced prevalence of delirium. These results suggest that delirium prevalence is significantly higher in diabetes patients and that metformin use may reduce delirium prevalence in diabetic patients.

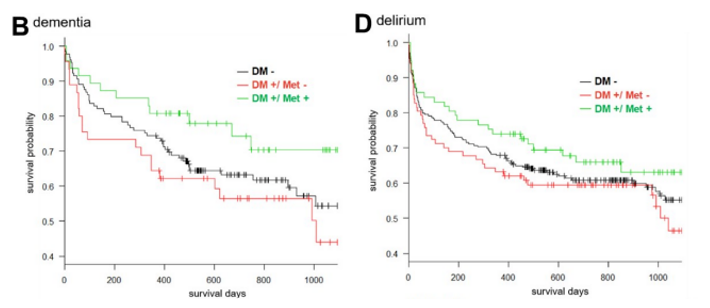

To get a better handle on metformin’s benefits, Shinozaki and colleagues measured whether it affects mortality. They found diabetes patients who took metformin had significantly lower mortality compared to diabetic patients who didn’t take metformin over a three-year period. Furthermore, there was no difference in mortality between diabetic patients who took metformin and individuals who don’t have diabetes. These interesting findings suggest that metformin use may increase the probability of survival in diabetic patients, comparable to those seen in non-diabetic individuals.

In search of further details regarding metformin’s benefits, Shinozaki and colleagues examined groups of individuals with dementia and delirium. Intriguingly, in both of these groups, diabetic patients who took metformin had a higher probability of survival during a three-year period than diabetic patients who didn’t take metformin and even non-diabetic individuals. These findings highlight the possibility that metformin may increase survival probabilities in multiple patient populations.

“Our data showed this potential benefit of metformin. The question is whether people without [type 2 diabetes] should start taking metformin,” said Shinozaki and colleagues.

Exploring Metformin’s Applicability Outside of Diabetes

The Stanford-based team suggests the possibility of administering metformin to patients undergoing major surgery, like cardiac, neuro, or orthopedic surgery. Future clinical studies on metformin use and mortality for these patient populations could one day reveal that metformin improves survival.

This also brings into question whether metformin could even be used to treat aging itself. Metformin is known to activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a protein that enhances cellular metabolism and mitochondrial health. Moreover, metformin inhibits the protein mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which regulates growth. Cell pathways involving AMPK and mTOR are known to influence aging processes, so metformin could exert anti-aging effects by influencing the activity of these proteins.

Limitations to the study include the short, three-year duration during which mortality was evaluated. Moreover, the study only examined overall metformin use and didn’t evaluate varying effects of metformin at different doses, as goes with all studies of this kind that analyze data from the past (retrospective study). For this reason, none of the interventions could be controlled, and no cause-and-effect relationships could be inferred.

Model: Human with an average age of 68.6 years

Dosage: Metformin use at unspecified dosages