Spanish Study Suggests Eating Low Phosphate Foods Like Fruits and Vegetables Could Alleviate Muscle Decline

Both a low phosphate diet and Velphoro — a phosphate lowering drug — mitigate features of muscle aging, including muscle strength and physical performance, in mice.

Highlights:

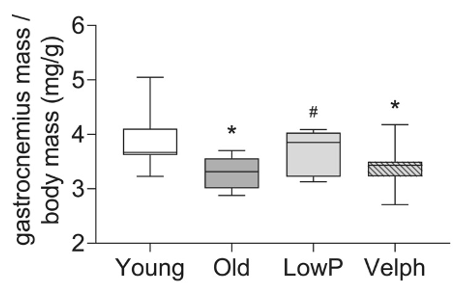

- A low phosphate diet (LowP) but not Velphoro increases the muscle mass of aged mice.

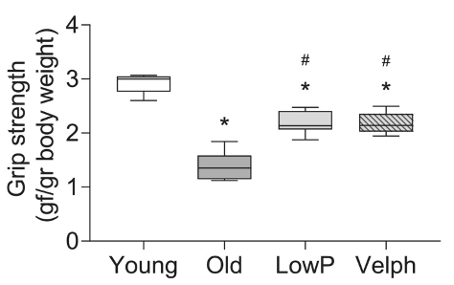

- Both LowP and Velphoro increase the strength of aged mice.

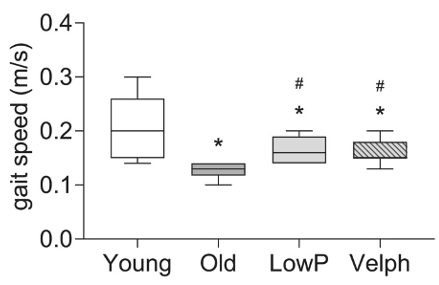

- LowP and Velphoro improve the physical performance of aged mice.

Phosphate is within every cell of our body, found most abundantly in our bones, along with the more familiar mineral calcium. Phosphate forms the backbone of our DNA, modulates pH, and participates in many cellular processes. However, too much phosphate is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality, and accelerated aging.

Now, researchers from the Universidad de Alcalá in Spain present, in the Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia, and Muscle, data suggesting phosphate levels increase with age and contribute to features of muscle decline, including reduced muscle mass and strength. Their findings suggest that lowering phosphate could have therapeutic value when it comes to muscle aging.

Lowering Phosphate Increases Strength and Performance

Our phosphate levels are affected by the food we eat, so consuming less phosphate-containing foods can lower our phosphate levels. Another option for lowering phosphate is by using the pharmaceutical phosphate binder Velphoro, originally developed to treat chronic kidney disease. Therefore, to determine if lowering phosphate ameliorates muscle aging, Alcalde-Estevez and colleagues fed old mice either LowP (0.2 % phosphate) or a standard diet with 5% Velphoro. These mice were compared to young mice and aged mice fed a standard diet (0.6% phosphate).

Muscle aging encompasses a progressive shrinking of the muscles called atrophy. To assess this feature of muscle decline, Alcalde-Estevez and colleagues measured the mass of the gastrocnemius, the largest of the two calf muscles. They found that muscle size was partially recovered by LowP but not Velphoro treatment, suggesting that LowP but not Velphoro can prevent age-related muscle atrophy.

Another feature of muscle aging is a progressive loss of strength. To assess muscle strength, Alcalde-Estevez and colleagues measured grip strength. The researchers measured grip strength by having their mice grasp a specialized bar that transduces and amplifies force. They then normalized this force value to the body weight of each mouse. The results showed that grip strength was greater in both the LowP and Velphoro groups, suggesting that lowering phosphate levels can prevent age-related muscle weakness.

With muscle weakness comes a loss in the capacity to perform movements. To assess physical performance, Alcalde-Estevez and colleagues measured gait speed. To do this, mice were placed into a catwalk and the velocity at which the mice moved was calculated based on distance and time. It was found that both LowP and Velphoro increased gait speed, suggesting that lowering phosphate can mitigate age-related losses in physical performance.

Kidney Aging Contributes to High Phosphate Levels

Aging is illy defined but can be described as the slow deterioration of the organs and tissues. In the case of the kidney, its deterioration can lead to chronic kidney disease, whereby the kidney can no longer filter blood properly. Usually, our kidney reabsorbs phosphate from our bloodstream, keeping (blood) phosphate levels low. However, phosphate reabsorption is hindered with chronic kidney diseases, which is most prevalent in aged individuals.

Is Consuming Less Phosphate-Containing Foods a Good Idea?

The findings of Alcalde-Estevez support that phosphate levels are elevated in old age and that reducing dietary phosphate can decrease these blood phosphate levels. Furthermore, reducing dietary phosphate could mitigate muscle aging.

“These results support the importance of restricting phosphorus (phosphate) intake for improving muscle structure and function during aging in mice. In humans, a study has correlated dietary phosphate intake with some accelerated aging signs,” state the authors.

According to Mayo Clinic, the best way to reduce dietary phosphate is to avoid foods like fast foods, packaged and convenience foods, processed cheese, processed meats, and soda. These recommendations are for individuals with kidney disease, but avoiding these foods, in general, seems like a good idea. Additionally, plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, and grains are low in phosphate, so the high-phosphate foods mentioned above could be replaced by nutrient dense plant-based foods.

Model: 24-month-old male C57BL/6 mice

Dosage: low phosphate diet (0.2% phosphate) for three months