Socializing is Crucial for Both Humans and Animals to Live a Long and Healthy Life

During these times, when most socialization is happening remotely, new studies point out that a lack of social support can negatively impact one's well-being and lifespan.

It has been two months since local governments issued the stay-at-home order across the U.S. to protect the health of residents by slowing the spread of COVID-19. As government and healthcare experts urge citizens to implement social distancing, they also stress the importance of “staying connected while staying away.”

Socialization is not only crucial to our mental health, but it also impacts us physically. A new review study published in the journal of Science, revealed how social connections are among the strongest factors in determining health and longevity in social animals.

“In both humans and other social animals, measures of social integration and social support have been shown to predict better health and/or longer lifespans,” said co-author Jenny Tung of Duke University in an interview with Inverse. Adverse social experiences elicit biological responses that negatively impact animals’ health and shorten their lifespans.

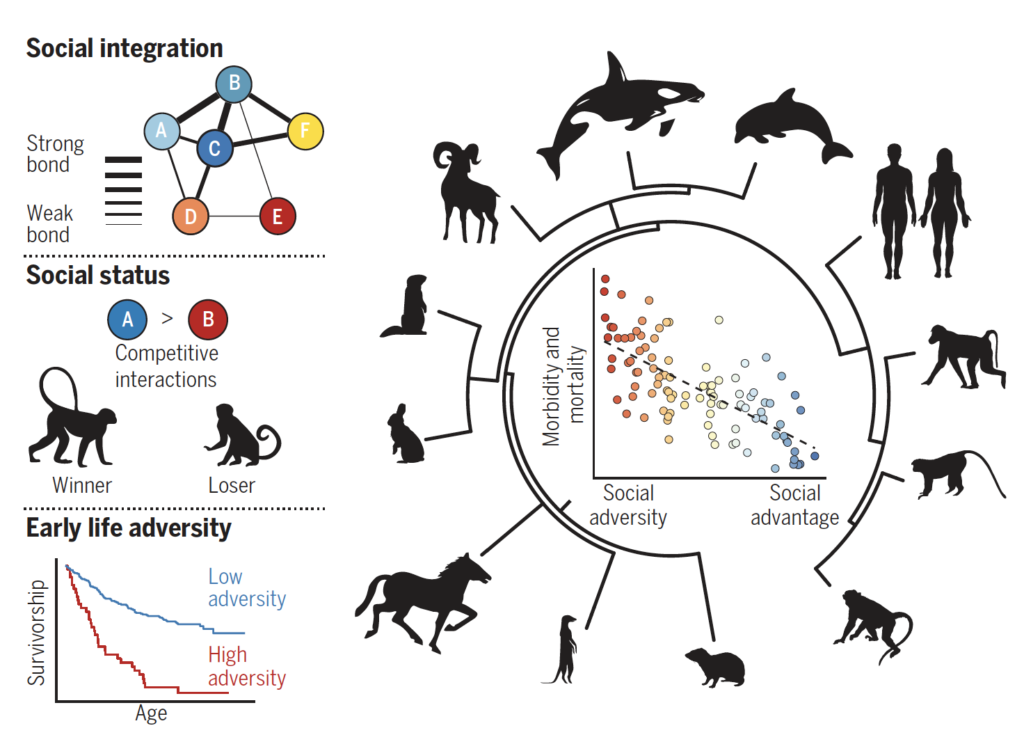

Social adversity is closely linked to health and mortality outcomes in humans, across the life course. These observations have recently been extended to other social mammals, in which social integration, social status, and early-life adversity have been shown to predict natural life spans in wild populations and molecular, physiological, and disease outcomes in experimental animal models. Snyder-Mackler et al., Science, 2020

In humans, the link between social integration and mortality, one’s risk of death, is well-established across continents and ethnicity. Data from 308,849 individuals in a 2010 study indicated that individuals with stronger social relationships have a 50 percent greater likelihood of surviving, despite how one may die.

Another predictor for mortality is socioeconomic status, which impacts one access to healthcare, social support system and lifestyle. The earliest data from the UK starting in 1931, showed that the risk of death from heart disease was more than two times higher for men in the lowest social class than the highest.

In animals, wild rabbits, meerkats, baboons, and macaques all show survival advantage to higher social rank. Scientists found that low-status animals lacking social support in strict hierarchy societies tend to exhibit higher levels of stress-associated hormones. Other studies discovered that chronic stress caused by social status shortens male mice’s lives by 12.4 percent.

“These findings suggest that evolving highly social lifestyles, as we and many other species have done, generates strong dependencies between successfully navigating social relationships and how well our bodies do,” said Tung in the interview.

The reviewed studies suggested that chronic social stress social adversity can explain multiple pathological outcomes, including increased inflammation, tumor-like conditions, heart-related diseases, and accelerated aging. Understanding sociogenomics, how social interactions alter molecular changes within the gene, is the next step for scientists and government agencies to develop treatments and shape policies.

More than nine million people in the U.K. often or always feel lonely, according to a 2017 report published by the Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness. In response, the U.K. appointed its first Minister of Loneliness in 2018. In the same year, the World Health Organization (WHO) committed to acting on the social determinants of health.

Under the current COVID-19 pandemic, feelings of loneliness in isolation have intensified for many people. Over Memorial Day weekend, Americans across the country crowded beaches and partied, breaking health officials’ social distancing guidelines. The inherited memory of “socializing benefits health” might explain the urge for social connection despite warnings.

“I think the difficulty of being able to maintain social distancing policies speaks to our strong motivation to stay in social contact and reinforce our relationships with others,” said Tung in the interview. “We often tend to think of our social relationships as something we pursue in our ‘free’ time, but they may not be so discretionary after all.”