New Study Shows Rapamycin Restores Blood Flow to Aging Limbs

Rapamycin restores lower limb blood flow in aged mice and mouse models for Alzheimer’s and atherosclerosis with implications for treating neurodegeneration and heart disease.

Highlights:

- Feeding aged mice rapamycin increases their blood flow to reach that of young mice.

- In a mouse model for atherosclerosis — a disease involving hardening of the arteries, rapamycin treatment restores blood flow.

- Alzheimer’s model mice also see an increase in blood flow from treatment with rapamycin.

A lesser-known age-related disease with dire consequences called peripheral artery disease (PAD) is characterized by a decrease in lower limb blood flow. PAD often accompanies other age-related diseases like diabetes, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. However, there are few treatments for PAD, and more severe forms require amputation.

Now, researchers from the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the University of Texas Health Sciences Center report in GeroScience that rapamycin restores blood flow to the lower limbs of aged, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse models. Rapamycin is an FDA-approved immunosuppressant drug that inhibits mTOR, a nutrient-sensing complex that seems to be detrimental to health in old age.

Rapamycin Restores Blood Flow

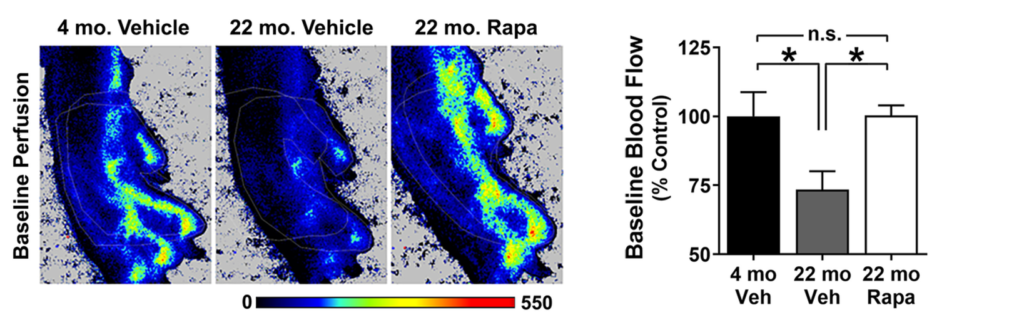

As we grow older, the blood flowing to our hands and feet declines, potentially leading to PAD. To determine if rapamycin restores blood flow, Van Skike and colleagues fed rapamycin to aged mice (22 months) and compared them to untreated aged mice and young mice (4 months). Skin blood flow was measured in real-time using laser speckle contrast imaging of the left hind paw.

The results showed that baseline blood flow (blood flow at rest) was fully restored by rapamycin treatment in aged mice. The researchers also measured blood flow in response to vasodilators — compounds that increase blood flow. To evoke blood flow, the researchers topically applied the vasodilators menthol and methyl salicylate. However, this did not lead to a significant increase in blood flow in rapamycin-treated aged mice.

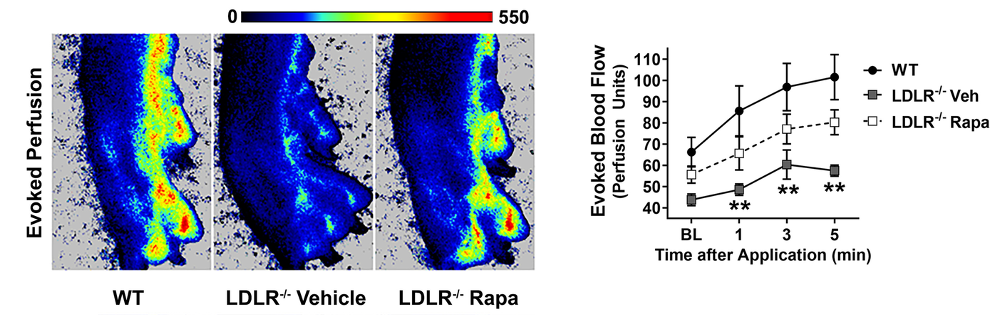

To determine if rapamycin restores blood flow in atherosclerosis, Van Skike and colleagues employed a genetically modified mouse strain lacking the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), which increases “bad” LDL cholesterol. These mice were fed a high-fat diet to induce atherosclerosis — plaque buildup in the arteries. Blood flow measurements showed that the atherosclerosis mice had reduced baseline and evoked blood flow, which were largely restored with rapamycin treatment.

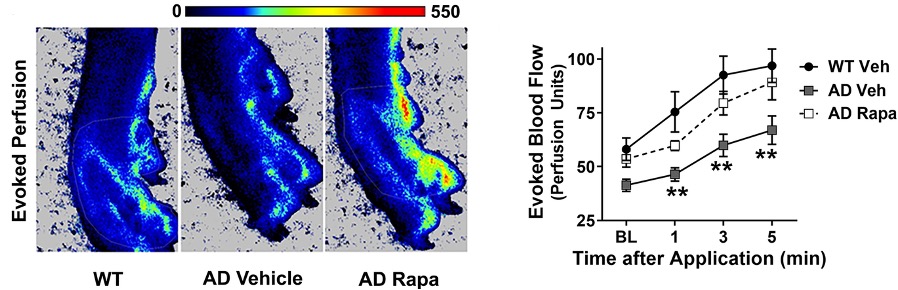

Some studies suggest that PAD incidence may increase in AD patients. To investigate if rapamycin restores blood flow in AD, Van Skike and colleagues utilized a mouse strain genetically modified to generate the human amyloid precursor protein (APP) in the brain, which leads to AD-like pathology. The results showed that blood flow was reduced in the AD mouse model even compared to aged (22 months) untreated mice. Still, rapamycin restored both baseline and evoked blood flow.

Previous studies have shown that rapamycin restores blood flow to the brain of aged, AD, and atherosclerosis mice while also improving cognitive and heart function, suggesting the prominent role of blood flow in these diseases and aging. The authors state:

“These data indicate that mTOR [mammilian target of rapamycin] mediates brain vascular disintegration and dysfunction leading to cognitive decline in normative aging and also cognitive dysfunction arising from distinct brain disease processes.”

Thus, rapamycin may be a good candidate for the treatment of AD and atherosclerosis.

The Many Anti-Aging Effects of Rapamycin

In mice, rapamycin has been shown to increase lifespan if taken late in life. It also increases lifespan if taken early in life but at the expense of growth. Additionally, rapamycin mitigates cognitive decline, mimicking caloric restriction (fasting), counters muscle weakness, and reverses stem cell aging. This, along with many other studies, could be why rapamycin is considered the most robust pharmacological agent for slowing aging.

Model: 22-month-old C57BL/6J mice, and Alzheimer’s and atherosclerosis model mice

Dosage: 14 ppm rapamycin in food