Scientists Discover Two Regulators that Could Halt Unhealthy Aging

We are living longer, but how do we stay healthy until the end of life? Chinese scientists report two new targets to help us age healthily.

During the 20th century, life expectancy in the U.S. had a 30-year increase, from 48 years to 77. But health doesn’t always come with longevity. A team of Chinese scientists reported in Nature that two genetic regulators prevent healthy aging, and targeting them could mitigate age-related deterioration like Alzheimer’s.

“Compared with great progress in understanding the regulation of longevity, little is known on the molecular mechanism underlying age-related behavioral declines,” said the author, Shiqing Cai from the Institute of Neuroscience and State Key Laboratory of Neuroscience at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, via email. “We are particularly interested in the topic because extending lifespan and keeping healthy are both important for the elderly.”

Led by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the team conducted genome-wide screenings in translucent, tiny, comma-sized roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans. They identified 59 genes that “provided the first global view of genes that may regulate age-related behavioral deterioration.” Among those genes, the team discovered two epigenetic regulators that accelerated behavioral decline in the roundworms — BAZ-2 and SET-6.

Our genes are not naked strips of DNA. They’re coiled around proteins decorated with epigenetic tags, which are crucial for our development. Some tags “silence” the genes by causing the DNA to coil tighter, making it harder for transcription factors to read the DNA sequence. Others loosen the DNA for transcription to activate the gene.

Unlike genetic mutation, epigenetic regulators like BAZ-2 and SET-6 act as “switches” that turn the epigenetic tags on and off without modifying the DNA sequences. The two switches caused the behavioral decline in the roundworms by reducing the function of the mitochondria, also known as the powerhouse of the cell.

By deleting either of the regulators or both, the team not only prevented the age-related decline in roundworms but also moderately extended their lifespan. The deletion even enhanced their capacity to resist harmful environmental factors such as UV light and heat.

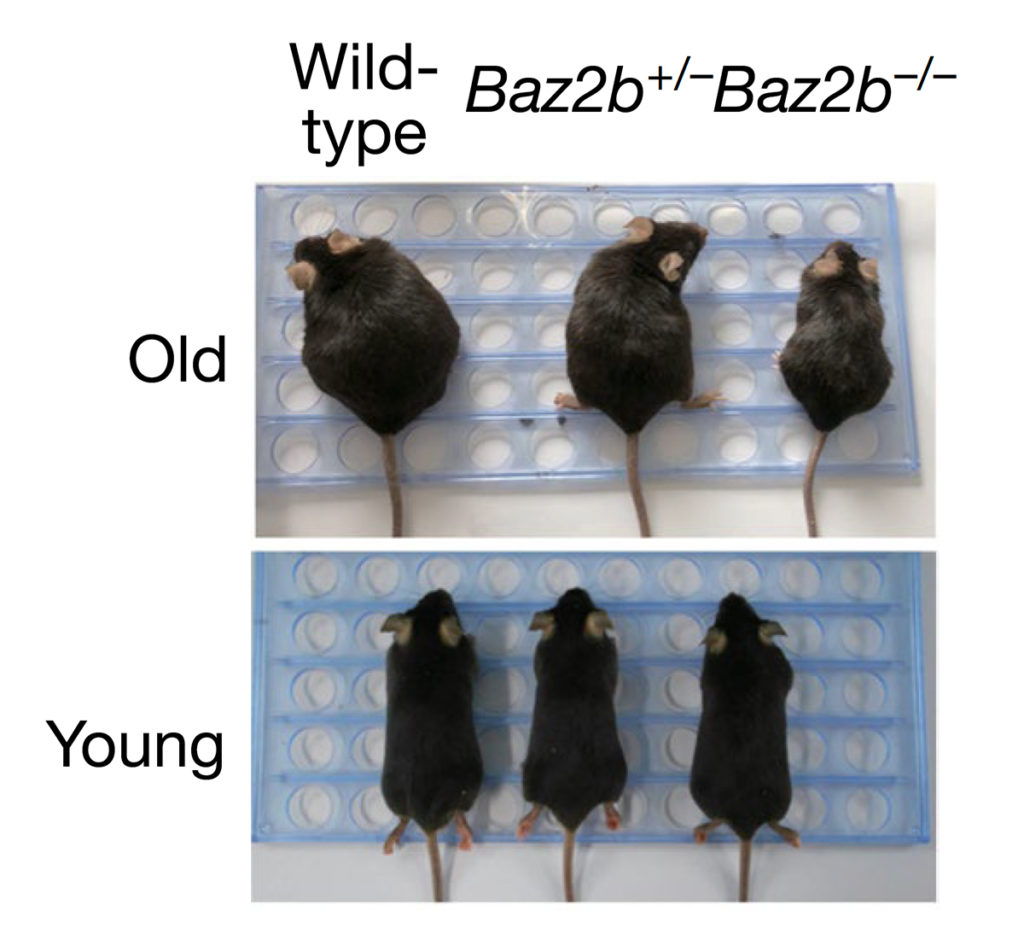

As mammals, we have our own versions of these epigenetic regulators, named Baz2b and Ehmt1. In male mice, deleting Baz2b improved cognitive behavior, prevented age-dependent weight gain, and averted mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial dysfunction is known as one of the triggers for unhealthy brain aging, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Many argue that results from animal research might not translate to humans; however, Cai and his team partially addressed the concerns by analyzing datasets in the human brain. They found that the expression of the two epigenetic regulators increases in the brain with aging. The levels of the regulators also increased with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another highlight of the study is that the deletion of the epigenetic regulators had no apparent effects on young animals, indicating the regulators impact the aging process later in life. The findings could lead to therapeutic interventions that could start then as we get older.

“As aging is a major risk for many human diseases, extending lifespan without simultaneously improving behavioral health will be a nightmare for both the society and families,” said Cai. The next step for the team is to “study whether BAZ2B and EHMT1 affect the progression of Alzheimer’s disease by using mouse models of Alzheimer’s Disease, and also will look for small molecules that can promote healthy aging.”