NMN Stifles Mouse Inflammation Response Like NSAIDs

Similar to anti-inflammatory drugs, treating immune cells called macrophages with NMN inhibits chronic inflammation that can cause cancer and insulin resistance.

Highlights

· NMN treatment alleviates the inflammatory response of immune cells called macrophages.

· Supplementing with the molecule also inhibits the buildup of inflammation-associated proteins, including COX-2.

· By dampening COX-2 accumulation, NMN targets inflammation like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

In a vicious cycle, inflammation in any body region like the joints activates immune cells called macrophages that secrete more inflammation-inducing substances to drive chronic inflammation. This perpetual inflammation can trigger diseases like insulin resistance and atherosclerosis, a buildup of plaque in blood vessels. To combat this detrimental chain of events, people use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like aspirin or ibuprofen. But prolonged NSAID usage can cause harmful side effects like intestinal bleeding. So, finding safer ways to treat inflammation is critical for people who have persistent inflammation to avoid injurious NSAID reactions.

Research by Deng and colleagues shows that treating mouse macrophage immune cells with 500 µM nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) reverses the buildup of inflammation-associated molecules, including proteins and byproducts of metabolism. In a study published in Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, the Tsinghua University researchers show that NMN inhibits macrophage inflammatory response. If future clinical studies determine that NMN regulates macrophage-perpetuating inflammation in humans, supplementing with the molecule may provide a means to sidestep NSAID side effects.

Inflammation Alters Metabolic Byproduct Abundance

Previous research has shown that administering NMN halts the progression of numerous diseases in rodents, which prompted the research team to test its ability to fight generalized inflammation. As far as NMN and inflammatory responses go, long-term treatment with the molecule has already been shown to suppress fat tissue inflammation in mice. Understanding whether NMN treatment restricts the macrophage inflammatory response is a critical starting point for determining whether people might use it for general inflammation one day instead of or in combination with NSAIDs.

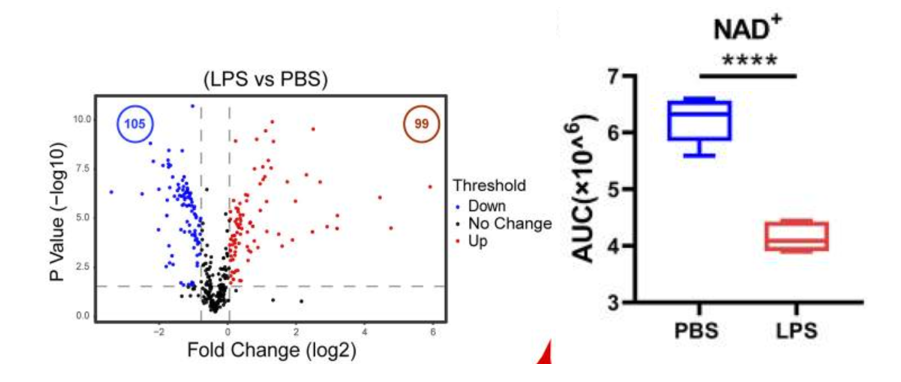

To begin their investigation, the researchers decided to examine what changes take place for metabolic byproduct molecule (metabolite) levels around macrophages during inflammation. For initiating a macrophage inflammatory state, the Tsinghua-based team applied large molecules from bacteria called lipopolysaccharides to the immune cells. Their metabolite measurements before and after the inflammatory stimulation indicated that about 22% of the 458 molecules examined increased while about 23% decreased.

Deng and colleagues took particular interest in the changing levels of NAD+, one of the metabolites measured. Its levels fell substantially after lipopolysaccharide inflammatory stimulation. The declining NAD+ levels that go along with inflammation begged the question of what effect increasing NAD+ would have on inflammatory processes.

NMN Reverses Inflammatory Metabolite Signature

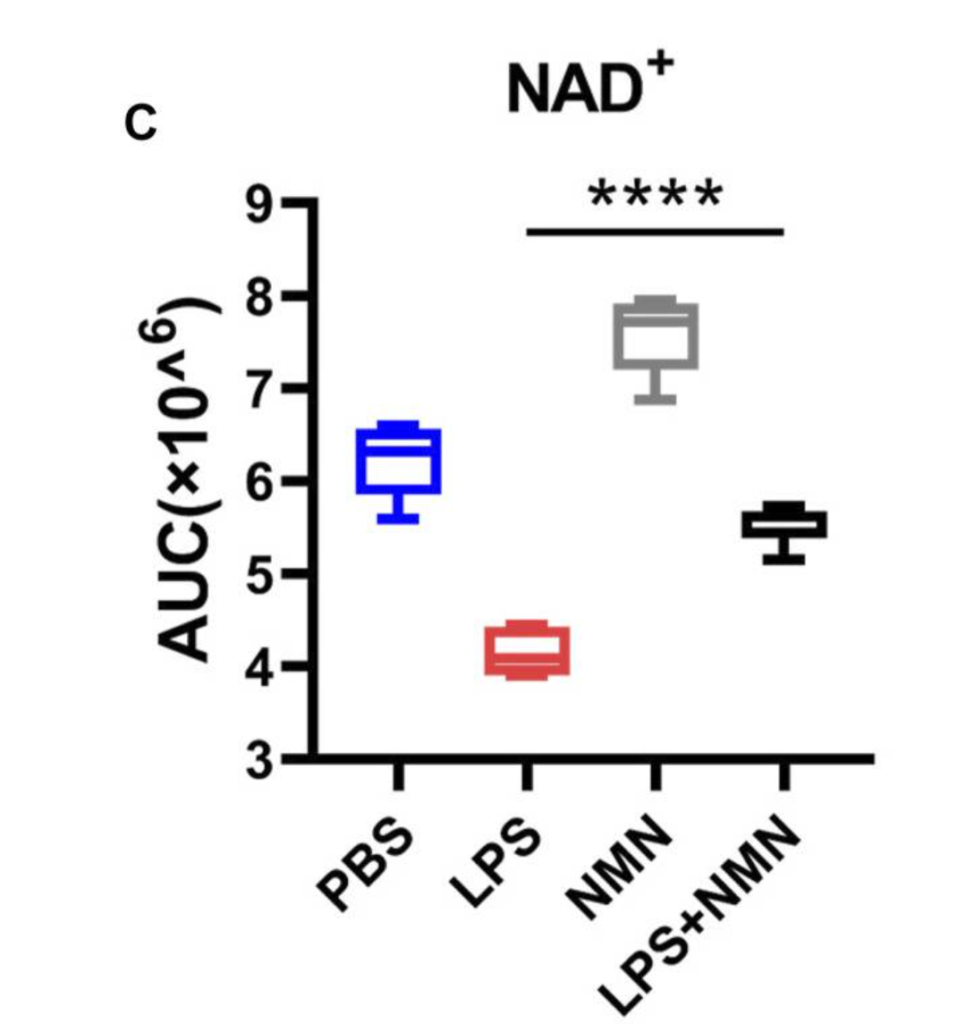

Next, Deng and colleagues treated the macrophages with NMN and lipopolysaccharide, which induces an inflammatory state, to see whether boosting NAD+ inhibits inflammation. Upon confirming that NMN does boost NAD+ levels in macrophages, the research team went on to show that NMN antagonizes the inflammation-associated changes in metabolite levels. In other words, it partially reversed the metabolite changes seen with inflammation. These findings suggest that NMN supplementation can inhibit inflammation.

NMN Reverts Inflammation-Associated Protein Levels

To verify that NMN treatment quells inflammation, Deng and colleagues then measured the levels of inflammation-associated proteins. With NMN treatment, the levels of all the inflammation-associated proteins measured decreased, further supporting that NMN alleviates the macrophage inflammatory state.

NMN Dampens NSAID Target Protein Accumulation

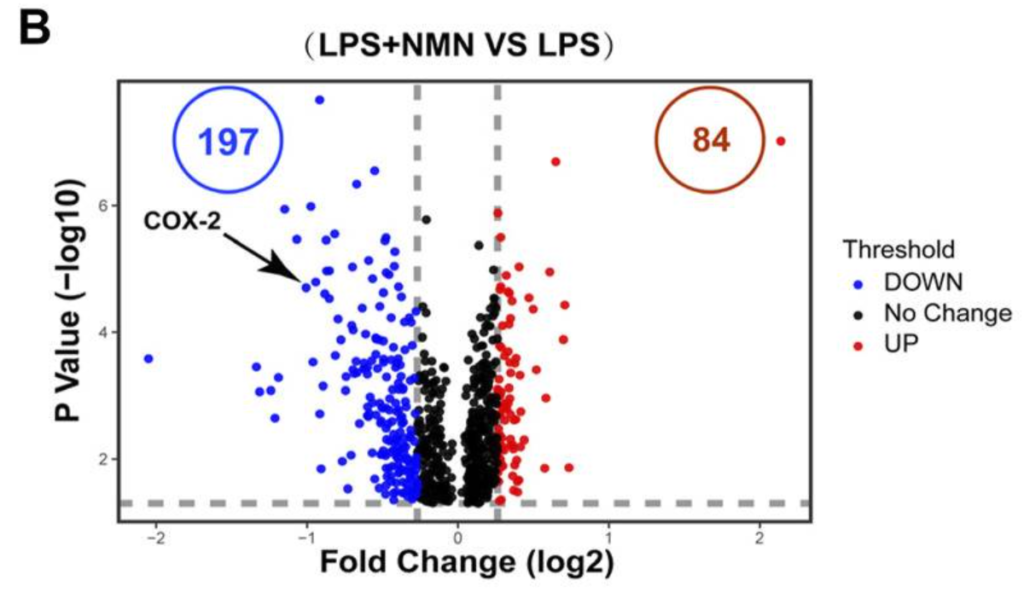

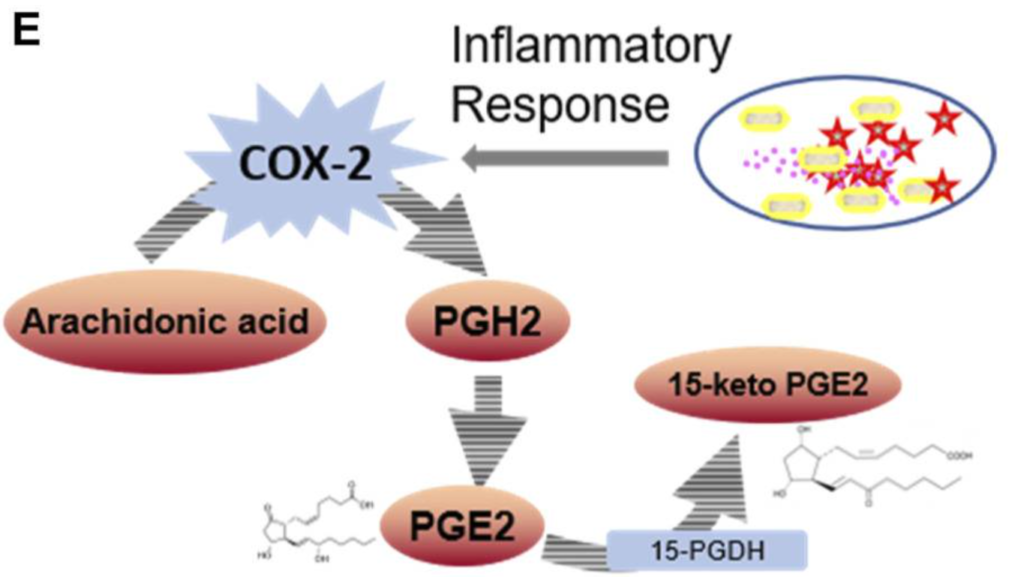

Deng and colleagues performed further analyses that indicate NMN suppresses levels of the protein cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an enzyme responsible for inflammation and pain and a known NSAID target. By inhibiting COX-2 levels, NMN may recapitulate some of the molecular activities of NSAIDs without giving adverse side effects.

NMN Dosages and Efficacy

So, how do we know that taking NMN is safer than prolonged NSAID administration? In a study showing that supplementing with NMN improves oxygen utilization in runners, up to 1200 mg/day was well tolerated with no known side effects. Two other NMN human studies, one that showed insulin sensitivity enhancements and the other showing muscle function improvements, used 250 mg/day. The results compiled to this point show that NMN may provide better tolerability compared to NSAIDs.

Will Future Studies Help Designate NMN to Replace NSAIDs?

“We revealed that the NMN supplementation decreased COX-2 expression,” said Deng and colleagues. “These results suggest NMN replenishment is an effective approach for chronic inflammation treatment.”

The biggest hurdle left is to see whether supplementing people with NMN dampens the macrophage inflammatory response since this study was done on mouse macrophages. The next step might be testing NMN in human macrophages and seeing its effects when inflammation is induced. If the same anti-inflammatory effects translate to the human macrophages, future studies could examine NMN’s capabilities in people who need prolonged NSAID treatments. Only then can we start seriously considering using NMN as an NSAID replacement.