Swiss Researchers Show NMN Could Help Teenagers Cope with Stress

A study from the Brain Mind Institute at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland show that nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) may help overweight kids and young adults going through puberty with sociability and early life stress by overriding signals from fat to the brain, a study shows

Highlights

- Adult mice stressed during puberty exhibit increased fat deposition and sociability deficits.

- Reduced levels of the NAD+ generating enzyme NAMPT in fat and blood link lifelong reductions in sociability to stress during puberty.

- Impairments in sociability and brain function are prevented by treatment with nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), an NAD+-boosting compound.

Being overweight as a child can lead to more health problems than meets the eye, such as poor social skills. The resulting behavioral interactions can result in great deals of stress during puberty, which can cycle back to cause long-term modifications in visceral fat deposition, further affecting the congeniality and stress of a teenager. But it’s unclear whether stress-induced changes in fat tissue yield signals to the brain that orchestrate behavioral changes.

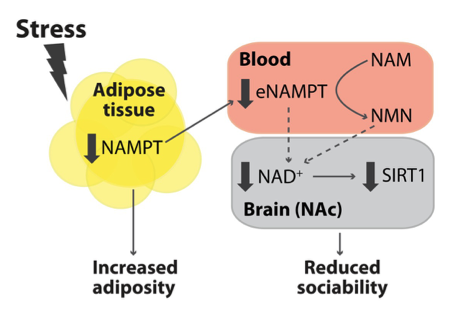

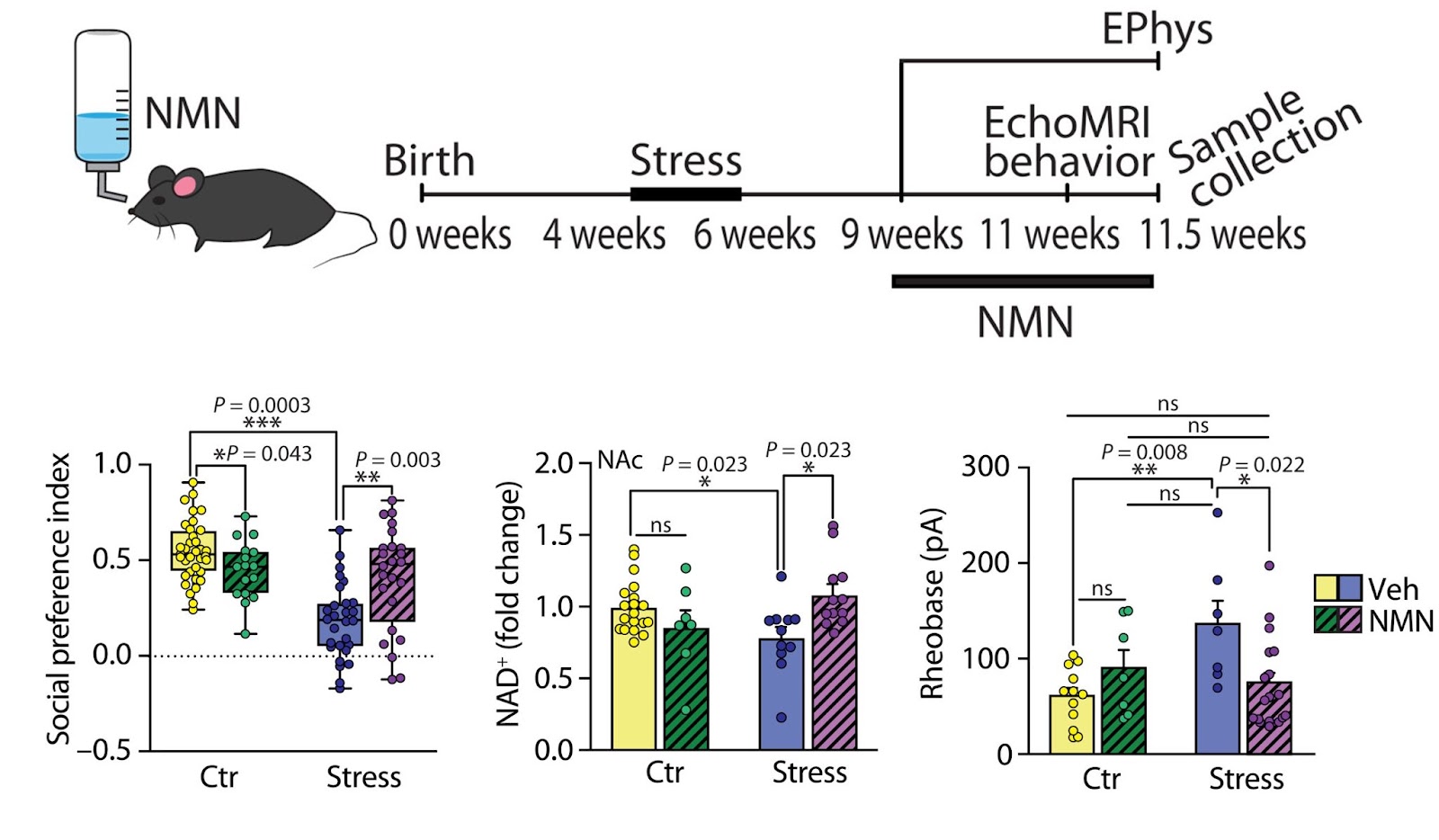

A study published in Science Advances shows that fat increases caused by stress during puberty reduce the communication of an enzyme called NAMPT from fat to the nucleus accumbens, a brain region known to encode the rewarding properties of social behavior. Researchers from the Brain Mind Institute at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland demonstrate that decreases in blood levels of NAMPT — which generates NMN, a direct precursor to the essential bioenergetic molecule NAD+ — contribute to lifelong reductions in sociability induced by peripubertal stress. However, drinking water supplemented with NMN (approximately 100 mg/kg per day) prevented these impairments in sociability and the function of the neurons in the nucleus accumbens. These findings highlight NMN and other NAD+-enhancing compounds as mediators of the reprogramming effects of early life stress on social behavior and the nexus between increased fat and these behaviors.

Fighting Fat to Fit In

Individual well-being and societal functioning are both dependent on social relationships. Reduced sociability in humans, such as social avoidance or retreat, can be a symptom of various psychopathologies. Even though social dysfunction negatively influences both individuals and society, the underlying causes remain unclear, and effective therapies are absent.

According to previous clinical and preclinical research, stress exposure throughout childhood and adolescence has been linked to increased fat buildup and obesity, as well as decreased sociability. “We know that stress can induce psychopathologies, including depression,” said senior author Dr. Carmen Sandi. “Some of the characteristic behavioral changes that you see in depression are alterations in the individual’s sociability, meaning that some depressed people tend to be more retracted, a bit social-avoidant; some can even develop social anxiety.”

But, it is unclear what behavioral changes in the overweight individual can describe the degree of obesity-related social retreat and whether metabolic processes might also explain social deficiencies.

Adult Mice Stressed During Puberty Have Increased Fat

Morató and colleagues created a mouse model that shows a link between increased fat deposition and sociability deficits that are frequently reported in humans, allowing them to investigate the mechanistic underpinnings of this association in animals. “What we focused here was in the reduction in sociability that you see in depression,” says Sandi. “We know also from epidemiological studies in humans that it can be linked with early life stress – peripubertal stress, which can program people to be less sociable. We explored whether alterations in fat composition induced by stress in early life could be responsible of inducing changes in the brain that, ultimately, would cause alterations in social behavior in a protracted manner,” says Sandi.

As part of the study, mice were stressed during puberty (peripubertal). Although maintained under a regular diet, these mice had reductions in lean mass and increased fat mass — without changes in body weight — in parallel to an enlargement of fat cells (adipocytes), mild glucose intolerance, and reduced muscle energy availability as adults. These findings indicate that peripubertal stress reprograms adult metabolism toward energy storage in the adipose tissue and is consistent with the view that early life stress leads to increased metabolic vulnerability.

NAD+ Signaling Is Impaired in Adult Mouse Brains Stressed During Puberty

The EPFL research team showed that mice stressed during puberty display a specific decrease in the circulating levels of compounds secreted from fat, including circulating NAMPT (eNAMPT) and leptin — a hormone predominantly made by fat cells that helps to regulate energy balance by inhibiting hunger, which in turn diminishes fat storage. Peripubertal stressed adult mice exhibited decreased NAD+ levels, specifically in a brain region that regulates social motivation called the nucleus accumbens. Congruent with these reductions in NAD+ levels in the nucleus accumbens, young adult mice submitted to peripubertal stress also exhibited decreased levels of gene activity in targets of SIRT1– an NAD+-dependent enzyme associated with increased longevity.

Morató and colleagues next showed that injection of NMN — an NAD+ booster that regulates SIRT1 activity — in the nucleus accumbens reverted the stress-induced social deficits in peripuberty-stressed mice. In contrast, co-injection with a SIRT1 inhibitor (EX527) abolished the effect, demonstrating the effect was due to SIRT1.

(Morató et al., 2022 | Science Advances) NMN administration in the nucleus accumbens prevents sociability deficits induced by peripubertal stress in male mice. (A) Control and stressed mice were implanted with guide cannulas targeted toward the nucleus accumbens (NAc). (B) NAc NAD+ levels in mice injected with vehicle (Veh) or NMN (25 mM). (C) Infusion of the SIRT1 inhibitor EX-527 (EX, 0.5 mM) abolished the capacity of NMN to normalize social preference in stressed mice.

Aiming at a translational application, Morató and colleagues evaluated the therapeutic potential of a nutritional NMN intervention by putting NMN into the drinking water of the mice. In line with the results obtained from injection of NMN into the nuclues accumbens, nutritional NMN treatment normalized stress-induced reductions in NAD+ content and neuron activity in the nucleus accumbens as well as social behavior.

In another experiment, activation of NAMPT in the fat of adult mice normalized peripuberty stress-induced impairments in blood eNAMPT levels, NAD+ content in the nucleus accumbens, and social behavior. In addition, fatty tissue NAMPT gene activation decreased stress-induced fat buildup. Whereas NAMPT gene activation in fat tissue reduced fat buildup and completely rescued sociability deficits, injection of NMN or direct targeting of SIRT1 in the nucleus accumbens did not have an impact on body composition. These observations were essential to understanding the precise role of NAMPT in fat tissue.

NAD+ Boosting in Kids and Teenagers

This study uncovers a fat-to-brain pathway that mediates the association between increased fat deposition and sociability deficits observed in adult individuals submitted to stress during the peripubertal period. Morató and colleagues highlight NAD+ boosters as a promising strategy to revert behavioral deficits associated with alterations in fat metabolism, mainly if triggered by early life stress. However, the EPFL researchers caution that not much research has been performed on NAD+ boosting during peripuberty. “We have to be careful because we applied nutritional treatments in our study at adulthood,” said Dr. Sandi. “We’re not saying that stressed kids or adolescents should take NMN; it will be important to analyze first if they have reduced plasma levels of NMN or eNAMPT, and to perform targeted studies to see the efficiency of this approach for younger populations.”