New Study: Dietary Genistein Extends Mouse Healthspan and Lifespan by 10%

Mice-fed genistein—found in almost all leguminous plants, including soybeans and coffee beans—exhibited a 10% increase in mean lifespan, mitigated aging, and delayed morbidity.

Highlights:

- Genistein-fed mice demonstrated a 9.2% increase in maximum lifespan and a 10.0% increase in mean lifespan.

- Genistein decreased the incidence and severity of aging phenotypes and delayed morbidity.

- Microbiota from genistein-fed mice rejuvenated the aging gut and extended the lifespan of prematurely aging (progeroid) mice.

Research from the China Agricultural University in Beijing showed that dietary genistein promoted a healthier and longer life and was associated with a decrease in the levels of systemic inflammatory cytokines in aging mice. Also, genistein in the diet helped fix gut problems like intestinal inflammation, a leaky gut, and a lack of cell regeneration in the gut lining. Researchers have found that a change in the gut microbiota and its metabolites caused by genistein plays a key role in extending the healthspan of mammals and keeping their guts healthy as they age. The research was published in Pharmacological Research.

The Gut Microbiome and Aging

In the last few decades, more and more evidence has shown that the gut microbiota is a key part of how health and disease develop in people. Changes in the gut microbiota that come with getting older include a drop in microbiota diversity, a drop in the number of helpful microorganisms, an increase in the number of potentially harmful bacteria, such as Bacteroides, compared to Firmicutes.

Also, as people get older, their gut microbiota loses genes that make short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and secondary bile acids. SCFAs are the main metabolites produced by the microbiota in the large intestine and have protective effects on the immune, cardiovascular, and nervous systems and are also anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-diabetes, and anti-cancer. Secondary bile acids are needed for digestion and absorption of lipids, as well as uptake of cholesterol and fat-soluble vitamins.

Genistein has been found in almost all leguminous plants, including soybeans and coffee beans, and many studies have indicated that genistein can alleviate inflammation, modify gut microbiota, and improve the function of the cells that line the gut (epithelial barrier) in several animal models of intestinal diseases. Moreover, genistein is known to have beneficial effects on age-related diseases, such as neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, bone loss, and skin aging, but its precise role in maintaining the health of the aging gut remains to be elucidated.

Genistein Increases Lifespan Via Gut Microbiome

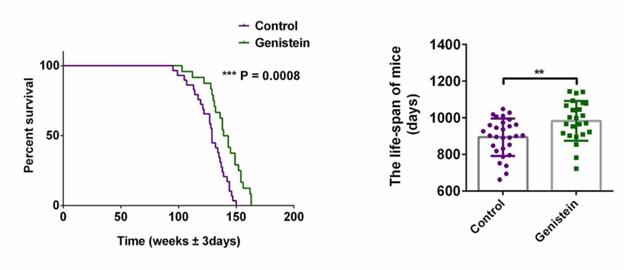

To assess the efficacy of genistein on longevity, Hou and colleagues subjected healthy mice to lifelong genistein supplementation (400 mg/kg) in food at 18 months of age, which roughly correlates to people in their mid- to late-50s. Interestingly, genistein-fed mice showed improved survival compared to control mice, with a 9.2% increase in the maximum lifespan and a 10.0% increase in the mean lifespan.

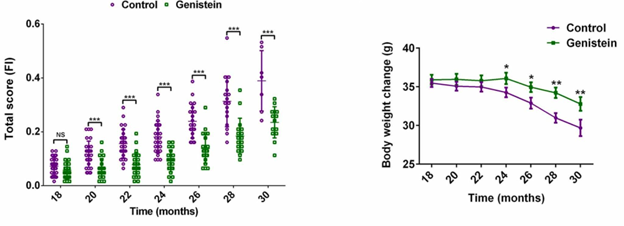

Then, Hou and his colleagues used 31 clinically relevant characteristics to figure out each mouse’s frailty score. This score is used to measure healthspan in the field of aging research. These analyses demonstrated that genistein decreased the incidence and severity of the aging phenotypes and delayed morbidity. Also, the treatment with genistein slowed down the loss of body weight and visible signs of aging, like a bad coat, losing color in the fur, and a stiffening tail.

Dietary genistein improved metabolic pathways in the gut microbiota that are involved in SCFA synthesis by a large amount, leading to increased SCFA production. Moreover, the relative abundance of a strain of “good” bacteria called Lachnospiraceae was positively correlated with the production of SCFAs and anti-inflammatory cytokines but negatively correlated with pro-inflammatory cytokines. These results showed that the genistein intervention may change the gut microbiota and its metabolites in a way that is important for the improvement of age-related frailty and gut dysfunction.

Based on the above results, Hou and his colleagues thought that changes in the gut microbiota caused by genistein might lead to better intestinal health and a longer healthspan and lifespan in older mice. To explore this possibility, the researchers performed fecal matter transplants from normal controls or genistein-fed aging mice on mice with an accelerated aging disorder known as progeria. These progeria mice, which have gut dysbiosis—the imbalance of gut microbiota associated with an unhealthy outcome—and age faster than normal, are perfect for studying how healthspan and gut microbiota are related.

On the one hand, the gut microbiota from control donors made progeria mice live shorter lives, have more leaky guts, and have more inflammation. On the other hand, the gut microbiota of donors who were given genistein and recipients who were given progeroid increased survival and improved the function of the intestinal barrier. In line with the genistein-fed experiments, transplants of feces from genistein-fed mice caused more Lachnospiraceae and more SCFA production.

This study gave the first evidence, as far as the authors know, that eating genistein changes homeostasis in the gut of an older mammal and increases their healthspan and lifespan.

Human Genistein Studies

The fact that there is a link between genistein and gut microbiota provides the reasoning to test whether genistein treats age-related weakness and gut problems. Several clinical trials have been registered to test the effects of genistein on humans. These trials have led to research publications.

Notably, a 2022 study led to a publication that suggested genistein could be used to treat people with early Alzheimer’s disease to delay the start of dementia. Another set of clinical trials led to a paper showing that osteopenic postmenopausal women who take genistein for 24 months improve their bone mineral density. These positive results show that these studies should be followed up with new studies with more patients as well as examining the role of genistein in gut health and aging.

Model: Naturally-aging and progeriod mice

Dosage: lifelong genistein supplementation (400 mg/kg) in food at 18 months of age