Japanese Study Suggests Ideal Protein Intake Ratio for Metabolic Health and Longevity

Low-protein intake leads to dysregulation of fat metabolism, while moderate intake lowers blood glucose and fat levels in middle-aged mice.

Highlights:

- A protein intake of 25% (percentage of total calories) or higher reduces liver fat deposition in middle-aged mice.

- Intake levels of 35% or higher reduce blood glucose levels.

- Protein intake levels of 45% increase circulating free fatty acid levels, an indicator of poor metabolic health.

Low-protein diets have been found to increase the lifespan of rodents, suggesting the same for humans. However, while low protein intake may increase our lifespan, it may not support life quality. This is because low protein may exacerbate age-related muscle loss — sarcopenia. Sarcopenia can lead to loss of independence due to mobility and strength problems and increase the risk of falls and fractures. Therefore, finding the optimal balance of protein may be crucial for living both a longer and healthier life.

Now, researchers from the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology in Japan have tested multiple ratios of protein intake in mice to find what is ideal for metabolic health and muscle preservation. As reported in GeroScience, Kondo and colleagues show that a protein intake percentage of about 35% is ideal for maintaining the metabolic health of middle-aged mice.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Yoshitaka Kondo explains, “The optimal balance of macronutrients for ideal health outcomes may vary across different life stages. Previous studies show the possibility of minimizing age-specific mortality throughout life by changing the ratio of dietary protein to carbohydrates during approach to old age in mice. However, the amount of protein that should be consumed to maintain metabolic health while approaching old age is still unclear.”

Moderate Protein Intake Optimizes Features of Metabolic Health

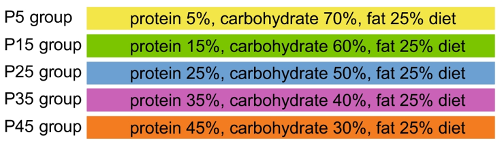

Young (6-month-old) and middle-aged (16-month-old) mice were separated into five groups of differing protein (from casein, an animal-based protein) intake levels. Lower protein was replaced with carbohydrates while fat was kept constant:

The results showed that protein intake did not have a significant effect on total muscle mass. However, strength was not assessed, so whether low protein intake leads to sarcopenia in this context remains unknown.

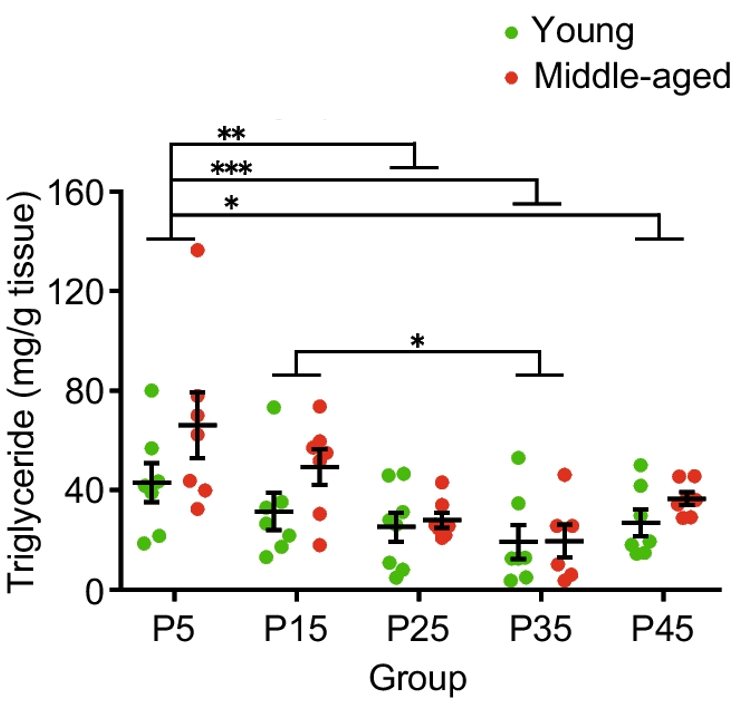

Fat deposits in the liver can lead to liver damage and increase the risk of problems like diabetes, heart attack, and stroke. Kondo and colleagues found that liver fat (triglyceride) content was higher in middle-aged mice compared to young mice. However, liver fat was reduced with protein intake levels above 25% (P25, P35, and P45 groups). These findings suggest that a moderate level of protein intake may deter fat accumulation in the liver, especially in middle age.

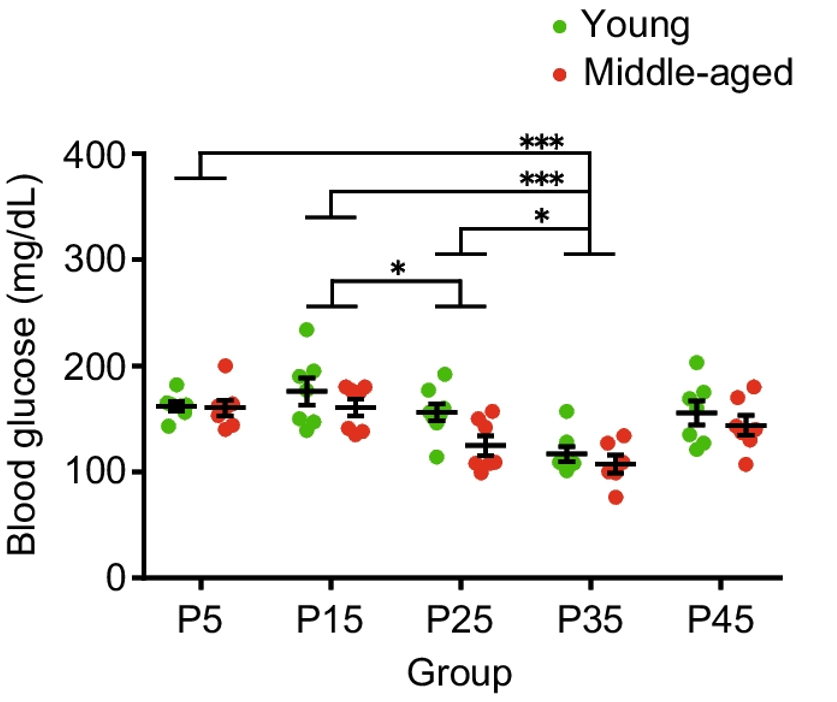

The Japanese researchers also looked at blood glucose levels, which can lead to diabetes when too high. Having diabetes increases the risk of problems like kidney failure and dementia. Interestingly, it was found that blood glucose levels were lower in middle-aged compared to young mice. Furthermore, a protein intake of 35% (P35) led to lower blood glucose levels when compared to protein intake levels below 35%. Since a protein intake of 45% appears to increase blood glucose levels, these findings suggest that a protein intake of 35% is ideal for reducing blood glucose levels.

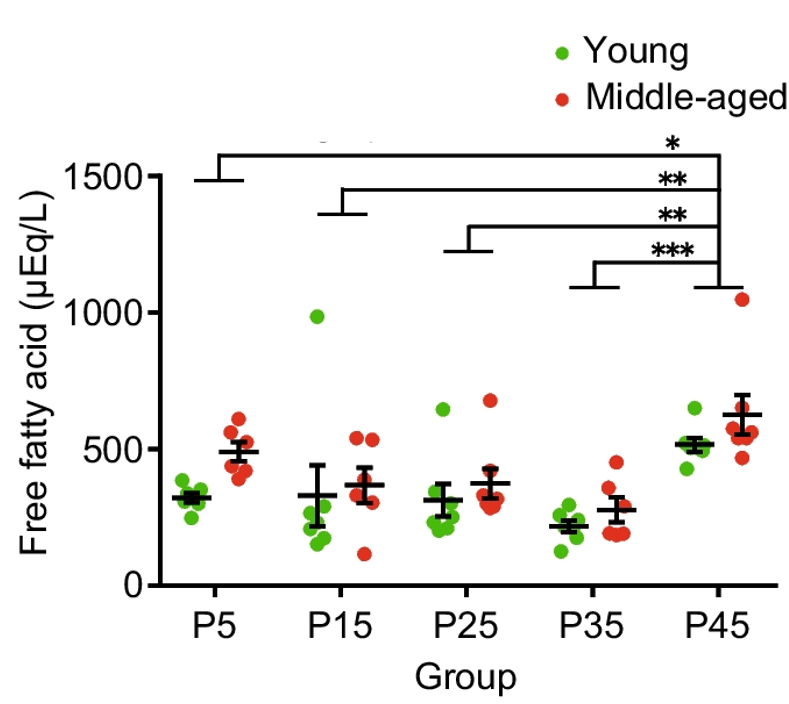

High circulating free fatty acid levels are associated with insulin resistance and can lead to high blood glucose levels. When looking at free fatty acids in the blood, Kondo and colleagues found that middle-aged mice had higher levels than young mice. Additionally, a protein intake of 45% led to an increase in free fatty acids. With the other measurements in mind, these findings suggest that a protein intake level of about 35% is ideal for optimizing liver fat content, blood glucose, and blood free fatty acids.

Overall, the findings of Kondo and colleagues suggest that a protein intake level of about 35% can improve metabolic health and slow metabolic aging. Since metabolic abnormalities are associated with the increased risk of deadly diseases, these findings also suggest that consuming moderate protein promotes longevity — a long life. However, since muscle strength was not assessed, it is unclear which level of protein intake could accelerate or mitigate sarcopenia. Notably, more research is needed to determine the ideal protein intake level per age.

Dr. Kondo remarks, “Protein requirements change through the course of life, being higher in younger reproductive mice, reducing through middle age, and rising again in older mice as protein efficiency declines. The same pattern is likely to be observed in humans. Therefore, it could be assumed that increasing daily protein intake in meals could promote metabolic health of people. Moreover, ideal dietary macronutrient balance at each life stage could also extend health span.”

How to Make Sure You’re Getting Enough Protein

When it comes to our diet, there are three macromolecules — proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. Protein and carbohydrates each provide 4 calories per gram, while fat provides 9 calories per gram. Therefore, the total amount of protein, fat, and carbohydrates we consume determines our total caloric intake. For example, if we ate 100 grams of each macromolecule in a day, our total caloric intake would be 1,700 calories ([100 g protein x 4] + [100 g carbs x 4] + 100 g fat x 9].

Our protein intake percentage is based on our total caloric intake. In the case of the 1,700-calorie example, our protein intake would be about 23.5% ([1,700 total calories/800 calories from protein] x 100). Knowing how much protein, fat, and carbohydrates you consume per day requires that you know the number of grams of each macromolecule in everything you eat. This is where food labels help. However, this can be time-consuming and tedious, and there are smart phone apps that can make it a lot easier, including My Fitness Pal.

Model: Middle-aged male C57BL/6NCr mice

Protein Intake: Diet consisting of about 35% protein as a percentage of total calories