UK Study Shows Older Workers’ Health Can’t Catch Rising Retirement Ages

The length of healthy working life from age 50 for men and women in the UK may not keep up with policy goals for state pensions.

Highlights

- Life expectancy projections from age 50 show a 4.10-year and 2.46-year increase in life expectancy for men and women, respectively.

- Healthy working life expectancy is projected to be 0.38 years and 1.08 years longer for men and women, respectively, in 2035 compared to 2015.

- The widening gap between healthy working life expectancy and life expectancy from age 50 suggests that working lives are not extending in line with policy goals.

Many countries have sought to lengthen working lives by raising the retirement or state pension age due to population aging and predicted improvements in life expectancy. For example, the UK state pension age will rise from 66 to 67 by the end of 2028, with further rises to 68 planned between 2037 and 2039. To achieve policy goals of extending people’s working lives, a significant proportion of the population must increase their healthy working life expectancy (HWLE) — the average number of years expected to be spent healthy (no limiting long-standing illness) and in paid work (employment or self-employment) from age 50 years.

However, a study led by researchers from Keele University in the UK shows that average HWLE gains in the UK are not expected to keep pace with average life expectancy gains. Published in Nature Aging, this study points to a likely decrease over time in the percentage of life expectancy from age 50 spent healthy and in work, resulting in a widening gap between HWLE and life expectancy from age 50. The low predicted growth in HWLE shows that working lives are not necessarily extending per policy aims, which could lead to an increase in older persons requiring benefits due to illness or unemployment.

Dr. Marty Lynch, the lead author of the study from Keele University, said: “Waiting for longer to receive a State Pension is unlikely to be made easier by additional healthy working years. Evidence-based initiatives to improve population health, wellbeing, and work opportunities are needed for working lives to be extended in line with policy goals.”

The Link Between Work and Health

Achieving policy objectives to extend later working lives requires a sufficient proportion of people in the population to be able to work for longer, along with appropriate job opportunities. Poor physical and mental health as well as employment levels, job opportunities, and the workplace environment are key reasons for early departure from the workforce — particularly in adults aged 50 and over. Socio-demographic and educational factors as well as sex and gender are also linked to health and work outcomes.

The links between health and work highlight the need to maintain a healthy workforce if policy changes to extend working lives are to be realized. The HWLE in England is less than ten years. Yet, the UK state pension age will increase to 67 by the end of 2028 with further increases to 68 expected to be brought forward to 2037–2039. Life expectancy gains may not translate to increasing HWLE since there is no consistent correlation between mortality rates and populations’ burdens of poor health.

Healthy Working Life Expectancy Lags Behind Lifespan Growth

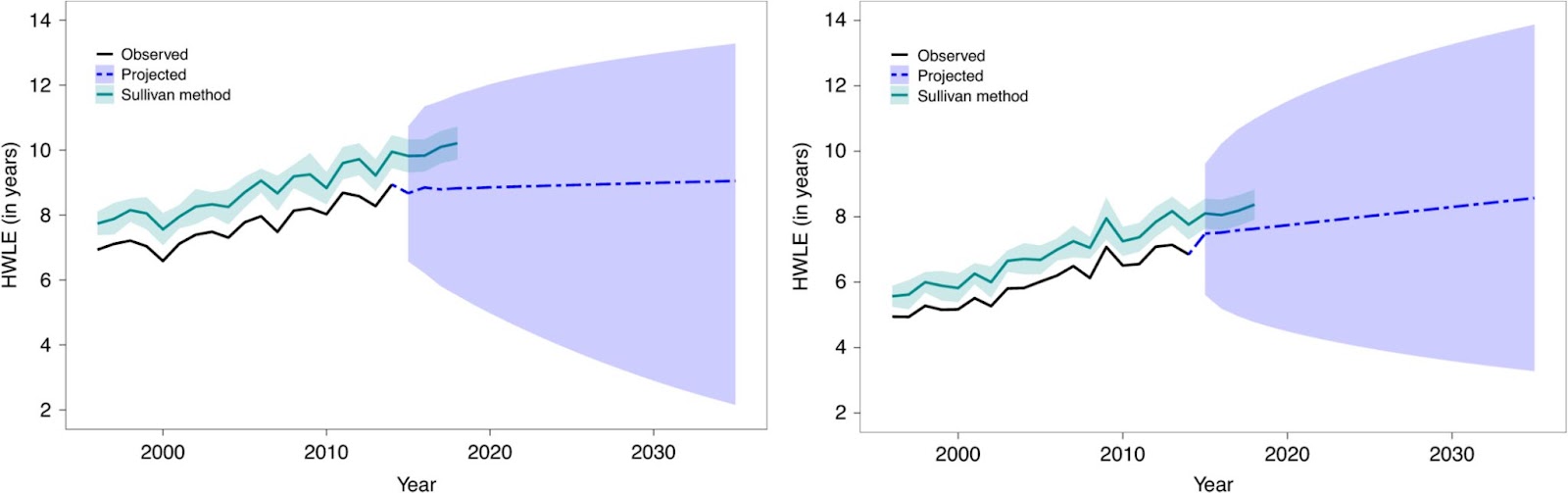

The small research team, primarily based out of the School of Medicine at Keele University in Keele, UK, projects that, while healthy working life expectancy has been extending in England in recent years, gains are projected to slow between 2015 and 2035. From 1996 to 2014, the average estimated increase per year in healthy working life expectancy from age 50 was 5.8 weeks for men and 5.5 weeks for women.

However, from 2015 to 2035, healthy working life expectancy gains were projected to slow to an average of 1 week per year for men and 2.8 weeks per year for women. Life expectancy projections from age 50 showed gains averaging 10.7 weeks (0.21 years) and 6.4 weeks (0.12 years) per calendar year between 2015 and 2035 for men and women, respectively. In other words, the healthy working life expectancy gains are predicted to be lower between 2015 and 2035 than the 4.10-year increase in men’s life expectancy and 2.46-year increase in women’s life expectancy expected from the age of 50.

(Lynch et al., 2022 | Nature Aging) Projections of healthy working life expectancy from age 50. Observed healthy working life expectancy (HWLE) (1996–2014, black line) and projected HWLE (2015–2035, blue dashed line) estimates for women shown with Sullivan method estimates (green line). The confidence intervals for the projected HWLE (light blue shading around the blue dashed line) are derived from uncertainty forecasts for changes over time in mortality and transition rates and in the prevalence of being healthy and in work at age 50.

Implications for Retirement Age Policy

This study has several important implications for policymakers and future research. Notably, the study finds that policies aimed at extending working lives are likely to fail unless they are accompanied by policies aimed at population health, job possibilities, and managing people’s health in the workplace. Whether people in England can work for longer depends on initiatives to enhance population health and access to acceptable jobs, especially since future cohorts of older people are projected to experience the early onset of numerous health issues (multi-morbidity).

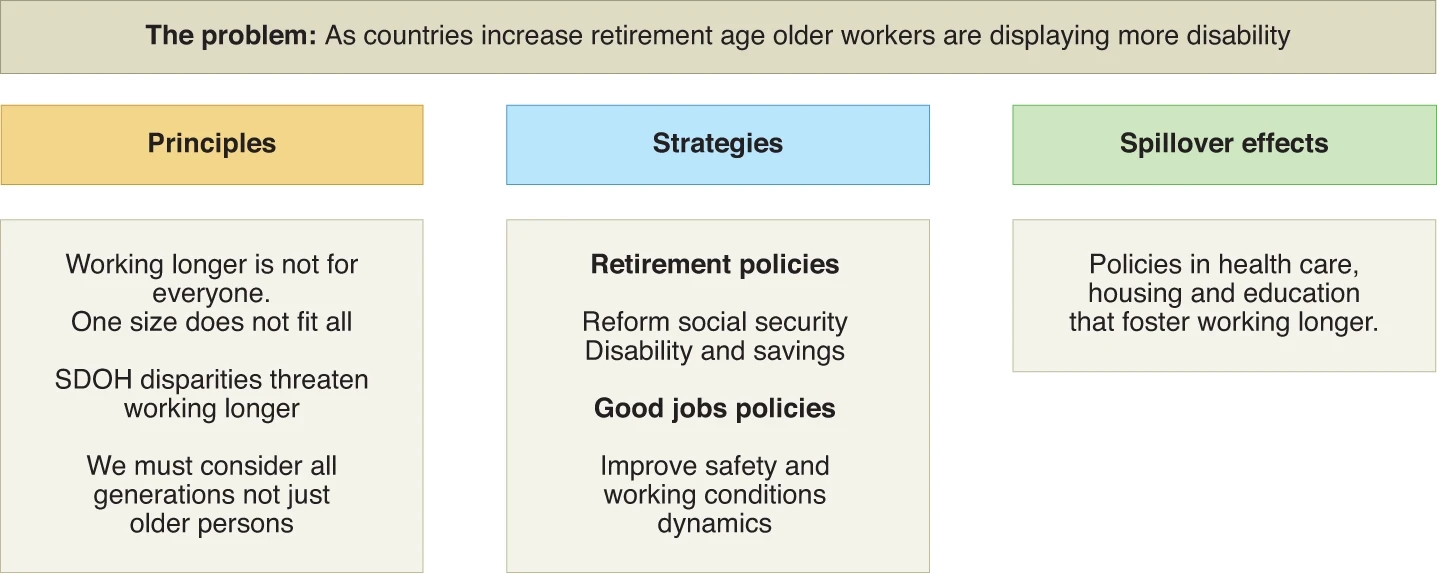

(Rowe & Berkman 2022 | Nature Aging) As countries increase the retirement age, older workers are displaying more disability. Direct and indirect strategies can enhance the likelihood of older workers remaining in the workforce longer and successfully retiring. SDOH, social determinants of health.

Dr. Ross Wilkie, the senior investigator in the study from Keele University, added: “The results suggest that further interventions and policies are required if people are to be healthy and in work until older ages. There is a broad range of targets for this, but three, in particular, to highlight would be employment opportunities that allow people to match their abilities with jobs as they get older; positive work environments that provide support and accommodations to maintain work participation; and third is a focused approach on health promotion and prevention of illness in workers, which often needs to be in partnership with employers, and there are already good examples of this in the UK and globally.”

More research is needed to examine the connections between healthy working life expectancy and population health, demographics, workplace, and lifestyle factors. Many factors, like climate change may have an unforeseeable impact on healthy working life expectancy in the following years; methodological research is required to account for the existing trends in lifestyle behaviors (for example, activity and obesity levels) and occupational characteristics.