Young Adults With High Blood Sugar and Low HDL Have Increased Alzheimer’s Risk

Boston University School of Medicine researchers show that lower HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol and higher blood sugar levels at age 35 are linked to a higher Alzheimer’s risk later in life.

Highlights

- This report demonstrates for the first time that low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and elevated glucose levels measured as early as age 35 are associated with Alzheimer’s later in life.

- These findings suggest that careful management of cholesterol and glucose levels beginning in early adulthood can lower Alzheimer’s disease risk.

There’s a saying that there’s no such thing as a free lunch — a no-cost situation. Now, research shows that may be literally true, at least when it comes to eating fatty and sugary foods in early adulthood.

Researchers from the Boston University School of Medicine show that careful management of cholesterol and glucose beginning in early adulthood can lower Alzheimer’s disease risk. This study indicates that from ages 35 to 50, high blood glucose levels and low blood high-density lipoprotein (HDL) — the good kind of cholesterol — and triglyceride (fat) levels are linked to Alzheimer’s risk. Published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, these findings suggest that early intervention to maintain healthy HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and glucose levels may improve cognition and lower Alzheimer’s risk.

“While our findings confirm other studies that linked cholesterol and glucose levels measured in blood with future risk of Alzheimer’s disease, we have shown for the first time that these associations extend much earlier in life than previously thought,” explains senior author Lindsay A. Farrer, Ph.D. The link between cholesterol fractions and pre-diabetic glucose levels in persons as young as age 35 to high Alzheimer’s disease risk decades later suggests that an intervention targeting cholesterol and glucose management starting in early adulthood can help maximize cognitive health in later life.

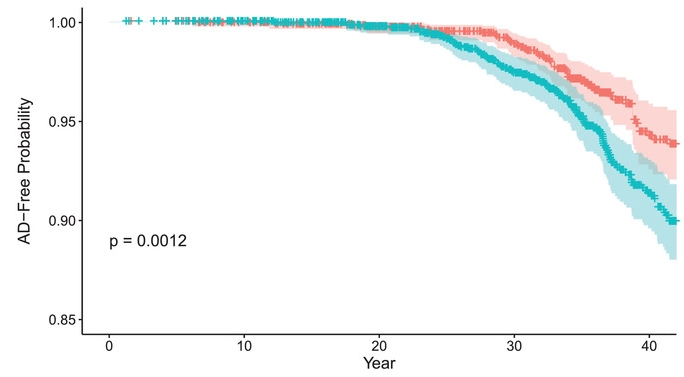

(Zhang et al., 2022 | Alzheimer’s & Dementia) Midlife glucose levels are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Cumulative probability of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)–free survival among individuals stratified into two clinically defined cutoffs for blood glucose (BG) concentration — below 100 mg/dL (orange) and above 100 mg/dL (cyan) — who were followed starting in early adulthood (ages 35-50 years). People with BG below 100 mg/dL had a higher AD-free probability than those with a BG above 100 mg/dL.

How Early Do Cardiometabolic Factors Affect Alzheimer’s Risk?

Early identification and treatment of individuals at risk for the common form of Alzheimer’s occurring after age 65 have been recognized as an important contributor to reductions in Alzheimer’s mortality and delaying the symptoms of the disease. The association of cardiometabolic risk factors — those concerning heart disease and metabolic disorders including diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, and elevated blood cholesterol levels — with cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s has been widely reported. But less is known about whether Alzheimer’s risk is associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in early adulthood. Addressing this question has added importance in light of the growing recognition that Alzheimer’s is a life-course disease.

In this study, Xiaoling Zhang and colleagues investigated the influence of cardiometabolic risk factors measured over more than 30 years on Alzheimer’s incidence in participants from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Offspring Cohort. This allowed the Boston University School of Medicine researchers to evaluate the effect of cardiometabolic risk on incident Alzheimer’s based on single time-point measurements from early, middle, and late adulthood.

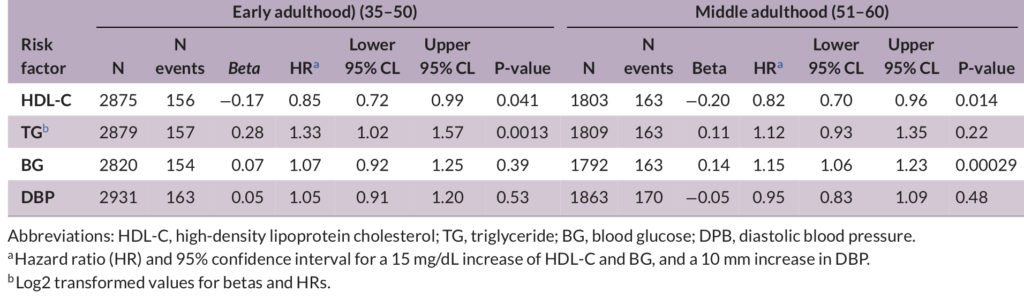

Low levels of HDL-C measured in early and middle adulthood were linked to a higher incidence of Alzheimer’s. The same was true for triglyceride levels, but only in early adulthood. On the flip side, blood glucose measured in middle adulthood was significantly associated with Alzheimer’s. Among persons in this age group, for every 15 mg/dL increase in blood glucose, the risk of Alzheimer’s increases by 14.5%. However, not all the cardiometabolic risk factors were linked to Alzheimer’s, including body mass index (BMI), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), systolic blood pressure, and smoking.

Management of Blood Cholesterol and Glucose Beginning in Early Adulthood Lower Alzheimer’s Risk

This study’s findings are consistent with a previous study showing that the cumulative number of cardiometabolic risk factors in midlife but not late life is associated with the presence of toxic protein aggregates called beta-amyloid in the brain in late life. Previous research on Framingham Offspring study participants has associated higher risk of coronary heart disease and metabolic syndrome with poor cognitive function at 55. Ultimately, this research brings us closer to the goal of determining the appropriate timing of vascular screening and interventions necessary to maximize benefits to cognitive and brain health.

These cardiometabolic factors may not be Alzheimer’s specific and may be of similar size or even larger for other forms of dementia. Studies of other cohorts containing much larger samples of non-Alzheimer’s dementia will be necessary to address this question. Further studies are also needed to enhance these findings and generalize them to non-European ancestry populations.