Fasting, Not Simply Calorie Reduction, Stimulates Age-Defying Metabolic Benefits in Mice

A University of Wisconsin animal study shows that extended periods without eating, not decreased calorie intake, drive aging-resistant metabolic benefits.

Highlights

· Reduced calorie intake boosts insulin sensitivity only when extended fasting periods are incorporated in mice.

· Fasting also extends lifespan in mice, while reduced calorie intake on its own diminishes lifespan.

· Extended periods without food confer metabolic and longevity-related benefits.

When trying to lose weight, typically with goals of living longer and healthier lives, people often target the number of calories they consume throughout the day. This idea that consuming fewer calories (caloric restriction) extends lifespan is backed by research in rodents; when calories are cut back about one-third of a typical diet, rodent lifespan substantially increases. What these studies don’t address is that calorie restriction schedules involve long periods without eating. Disentangling the longevity-promoting health benefits from calorie restriction on its own versus those from fasting has proven difficult, dropping the issue below scientific research’s radar.

Dr. Dudley Lamming and colleagues from the University of Wisconsin published a cutting-edge study in Nature Metabolism, showing that the fasting schedule is the determining factor in calorie restriction eating regimens that promotes metabolic benefits and lifespan extension in mice. Lamming and colleagues dissect, with measurements of metabolism and gene activity, calorie restriction’s influence on longevity, showing that calorie restriction reduces lifespan without fasting. These new findings run contrary to the idea that reducing calorie intake on its own provides these gains.

As Lamming and colleagues say in their publication, “…while ‘you are what you eat,’ it is equally true that ‘you are when you eat.’”

Calorie Restriction with Fasting Changes Metabolism

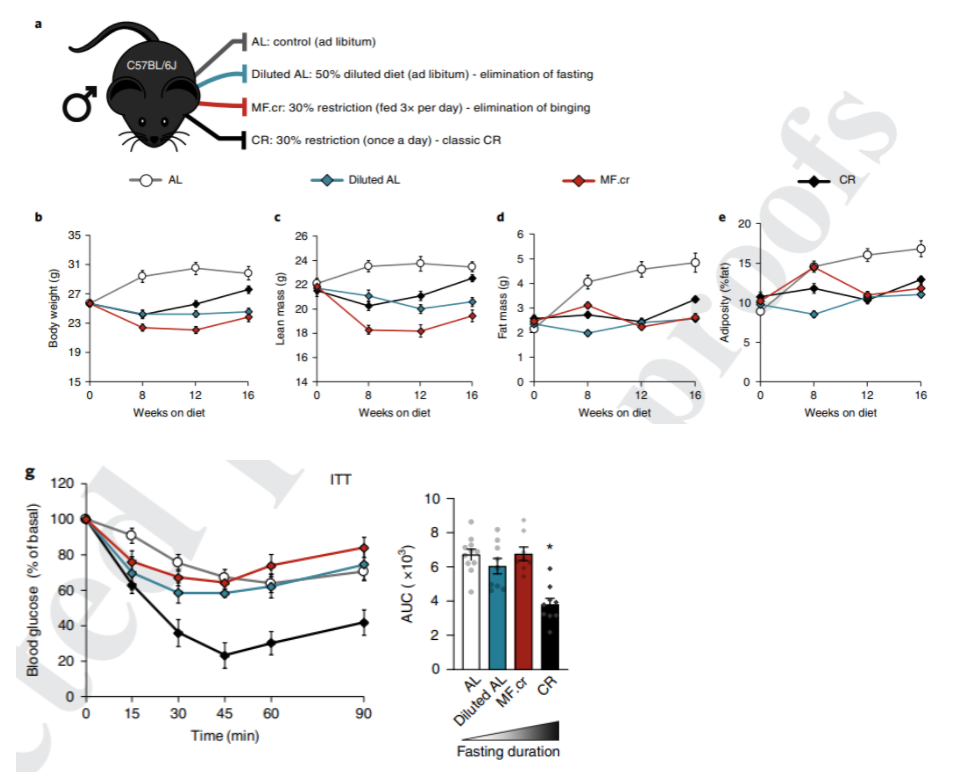

To uncover the root characteristics of dietary calorie restriction schedules that promote longevity, the Madison-based research team divided mice into four groups based on their diet. One of the groups ate whenever it wanted, another ate a diluted diet whenever it pleased, a third ate calorie-restricted meals three times a day, and a fourth ate a traditional calorie-restricted diet. These group divisions allowed the researchers to compare an unrestricted eating schedule to calorie restrictions without fasting and calorie restricted eating with ~22 hours of fasting per day.

To then examine how calorie restriction with and without fasting affects metabolism, Lamming and colleagues looked at measurements of body weight and insulin sensitivity. They found that, compared to feeding throughout the day, calorie restriction with or without fasting reduces body weight only to rebound later in the experiment with fasting. Interestingly, insulin sensitivity only significantly improved in the calorie-restricted group that underwent fasting. These findings suggest that fasting alone alters the way the body utilizes fuel in calorie-restricted animals since rebounded body weight and improved insulin sensitivity result from fasting.

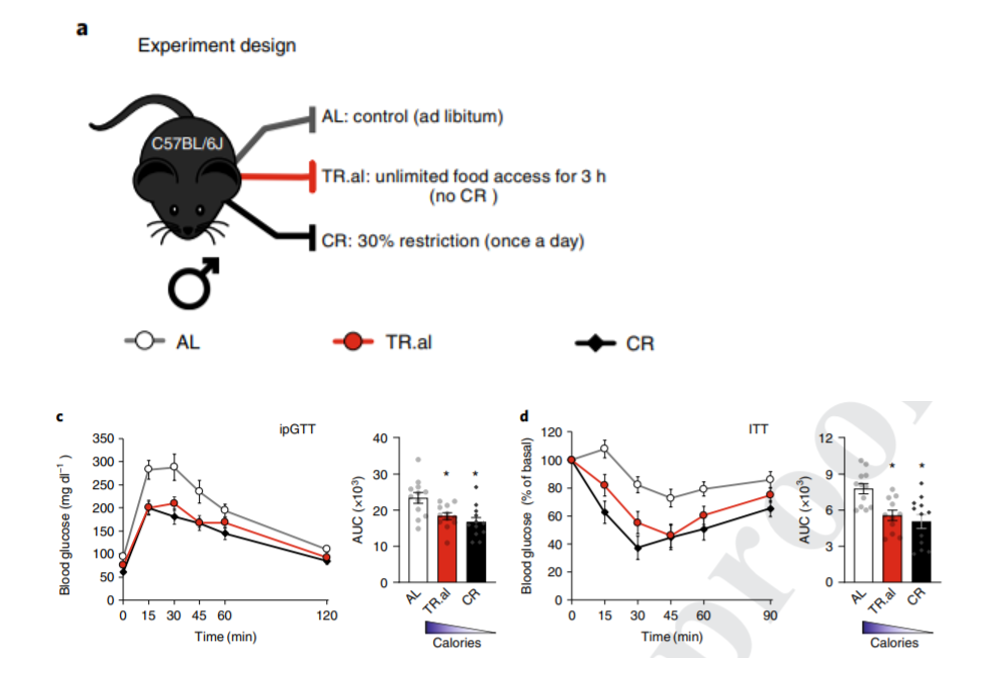

Fasting Without Calorie Restriction Enhances Metabolism

Since these findings suggest that fasting can enhance metabolism, Lamming and colleagues sought to examine whether fasting alone is sufficient to recapitulate metabolic benefits. This time, they divided mice into three feeding groups: one eating an unrestricted amount, one eating unlimited amounts for only three hours, and another undergoing caloric restriction. Regardless of calorie intake, both groups that underwent fasting displayed enhanced insulin sensitivity and reductions of the sugar glucose in their blood. These findings demonstrate that fasting alone, regardless of calorie intake reductions, can rehash the physiological benefits of caloric restriction.

After showing that fasting drives the metabolic benefits typically associated with caloric restriction, Lamming and colleagues wanted to find what molecular underpinnings are involved. By performing gene activity analyses, the research team showed higher activity in specific molecular pathways after fasting. These pathways included sleep-wakefulness (circadian rhythm), metabolism, insulin signaling, and, importantly, longevity-regulating pathways.

Reduced Calorie Diets with Fasting Prolong Lifespan

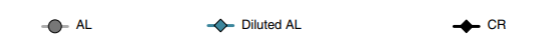

To then parse out the effect of fasting in calorie restriction-related lifespan extension, Lamming and colleagues compared longevity measurements in three more groups of mice. One group was fed however much it wanted, another fed however much it chose with a 50% diluted diet, and the last was fed a classic calorie-restricted diet with imposed fasting. The mice that underwent calorie restriction with fasting lived significantly longer than the other two groups, even though the group with a diluted diet also received a reduced quantity of calories. These findings support that lifespan extension results from fasting alone.

A limitation of the study comes from the lifespan extension test showing that fasting during caloric restriction induces enhanced longevity. The group of mice fed a 50% diluted diet had indigestible cellulose infused into the food, which may have adversely affected the physiology of the mice. Along these lines, mice fed the reduced calorie diluted diets had about a 9% reduced lifespan compared to mice fed as much as they wanted. Cellulose’s effects on gut health are not well understood, and it may adversely affect the microbial composition – the microbiome – of the gut to diminish lifespan.

Because of this limitation, it’s quite challenging to say whether reduced calorie intake without fasting leads to a reduced lifespan. Moreover, it makes comparing calorie restricted diets with fasting to calorie restricted diets without fasting very difficult. Even though gene activity analyses showed fasting stimulates longevity-promoting pathways, more longevity studies are needed to establish whether fasting on its own can extend lifespan in mice.

Another limitation was that the longevity testing was performed on male mice. Finding out whether fasting’s beneficial effects on lifespan apply to females will be important to see whether females may equally reap longevity benefits from extended periods without food.

Can Fasting Extend Human Lifespan?

“Mice that eat a normal amount of food in a short period of time, and as a result fast for a long time between meals, have metabolic benefits without having to reduce their calories,” said the publication’s principal investigator, Dudley Lamming, Ph.D.

The study’s authors urge caution, though, when applying these results to humans. In other words, while it may be tempting to start intermittent fasting routines today, you should make sure to consult with a physician before making any major dietary alterations. Nevertheless, perhaps it’s time for us to change the age-old adage to “You are when you eat.”