Fasting Increases Length of Life but Resilience Matters Too

A large study shows that lifespan extension from caloric restriction and intermittent fasting depends on genetic background, resilience, and immune health in mice.

Highlights:

- Dietary restriction — fasting and cutting calories — prolongs the lifespan of mice but with high variability.

- Resilience to stress is strongly associated with whether dietary restriction prolongs lifespan.

- Immune system health and genetic background are also strong determinants.

Cutting calories is the only natural way to lose weight. However, whether this strategy is conducive to longevity — living longer — has been brought into question. A new study suggests that our genes determine whether fasting or eating less food leads to a longer or shorter life.

Dietary Restriction Prolongs Lifespan

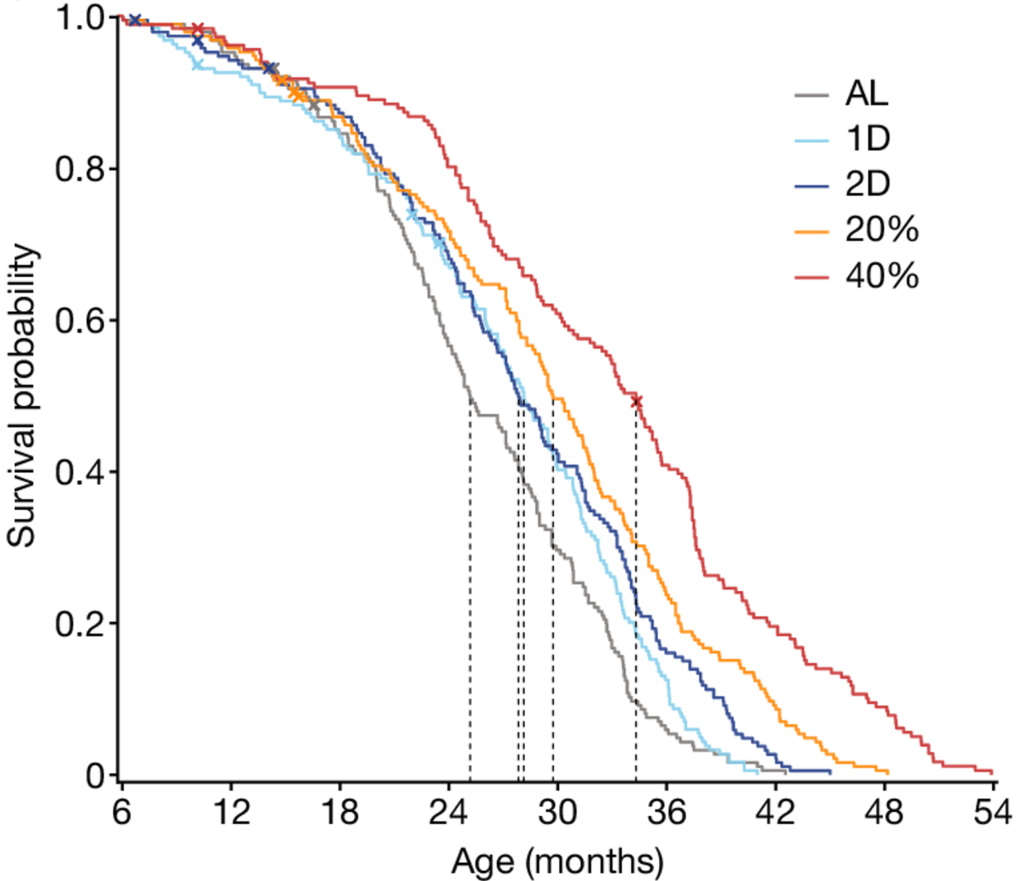

In one of the largest studies of its kind, researchers from Calico Life Sciences, a subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. (the parent company of Google), confirmed that several forms of dietary restriction triggered lifespan extension in female mice. The researchers divided genetically diverse mice into five groups:

- Mice fed ad libitum (AL) — as much or as often as desired.

- Mice fasted for one day a week

- Mice fasted for two days week

- Mice fed 20% less than the AL mice

- Mice fed 40% less than the AL mice

Compared to the AL group, the other four groups lived longer:

- Mice fasted for one day lived 11.8% longer

- Mice fasted for two days lived 10.6% longer

- Mice fed 20% less lived 18.2% longer

- Mice fed 40% less lived 36.3% longer

Importantly, the mice fasted for 1 day ate just as much as the AL mice and the mice fasted for two days ate only 12% less than the AL mice. These findings suggest that cutting calories is not the primary reason for lifespan extension. Indeed, fasting appears to be sufficient to prolong life expectancy. Moreover, the mice fed 40% less food also fasted for 2 days, suggesting that fasting and cutting calories had an additive effect.

Resilience to Stress and Lifespan

While on average the mice in each dietary restriction group lived longer, there was great variability. That is, some of the mice in each restricted group did not have a longer lifespan. To determine why this was the case, the researchers took over 700 different measurements from the mice. Notably, they found that the mice that retained the most weight had longer lifespans, countering the notion that dietary restriction works through weight loss alone.

Furthermore, during data collection, the mice were handled by the researchers, which caused stress and short-term weight loss for the mice. In addition to handling, fasting and caloric restriction are also physiological stressors. The researchers found that short-term weight loss, an indicator of stress, was strongly associated with a shorter lifespan. These findings suggest that resilience to stress is a key determinant of whether dietary restriction can prolong lifespan.

Immune System, Genetics, and Lifespan

Other than resilience to stress, the researchers found several other indicators of a longer or shorter lifespan. They found that bad posture and disordered walking patterns were associated with a shorter lifespan, whereas having fewer tumors was associated with a longer lifespan. Interestingly, lower fasting blood glucose levels were not associated with longer lives.

Moreover, immune system health was associated with longevity, especially in the mice fed 40% less food. Additionally, less variability in red blood cell size was strongly associated with longevity. Furthermore, the researchers found that up to 24% of the variability in lifespan could be accounted for by genetic background. What’s more, 23% of this genetic contribution was attributed to one location on chromosome 18. Variations in this region could lead to a shorter lifespan.

Does This Translate to Humans?

Whether fasting and caloric restriction can prolong the lifespan of humans is unclear. Mice have different metabolic rates and die for different reasons than humans. While mice usually die of cancer, humans most commonly die of heart disease. Furthermore, in humans, muscle loss is associated with a shorter lifespan. In the current study, all the mice lost muscle mass, which is concerning for human translation. Overall, it is likely that the effect of fasting and caloric restriction on humans is highly individualized, causing harm and/or benefit.