Enzyme-Mediated NAD+ Production is Essential for the Quality Control of Aged Eggs

As a woman ages, so does her eggs. The decline in the quality and quantity of eggs results in a drop in fertility, but raising the NAD+ level may be a novel way to improve the effects of aging on the egg.

The number of eggs in a woman is set before she’s born. As a fetus in its mother’s womb, females have about 6 million to 7 million eggs. From then on, the number of eggs only drops. At birth, the baby girl has approximately 1 million eggs, when she hits puberty, about 300,000 remain. Not only does the number of eggs decrease as women age, but the quality of them also declines, impacting one’s fertility.

“After 37, fertility declines at an [increasing] pace, so that by the time a woman is between 40 and 45, her fertility has decreased by as much as 95%,” said Dr. Sherry Ross, a women’s health expert and the author of “she-ology,” in an interview. “The ticking of the biological clock becomes louder at 40, and by 45, it can be deafening along with pregnancy complications.”

About 10 percent, or 6.1 million, women in the US aged 15 to 44 have difficulty becoming pregnant or staying pregnant, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). But in a study, a team of Chinese scientists successfully improved the quality of aged mice eggs by increasing the levels of a molecule — nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) — through mediating an enzyme.

NAD+ Improves Egg Quality

From tiny amoebas to 37-story tall redwoods, NAD+ is one of the most abundant molecules in organisms. The molecule plays a crucial role in energy production and maintaining cell integrity through several molecular pathways. But as organisms age, the level of NAD+ decreases throughout the body, including oocytes, also known as immature eggs.

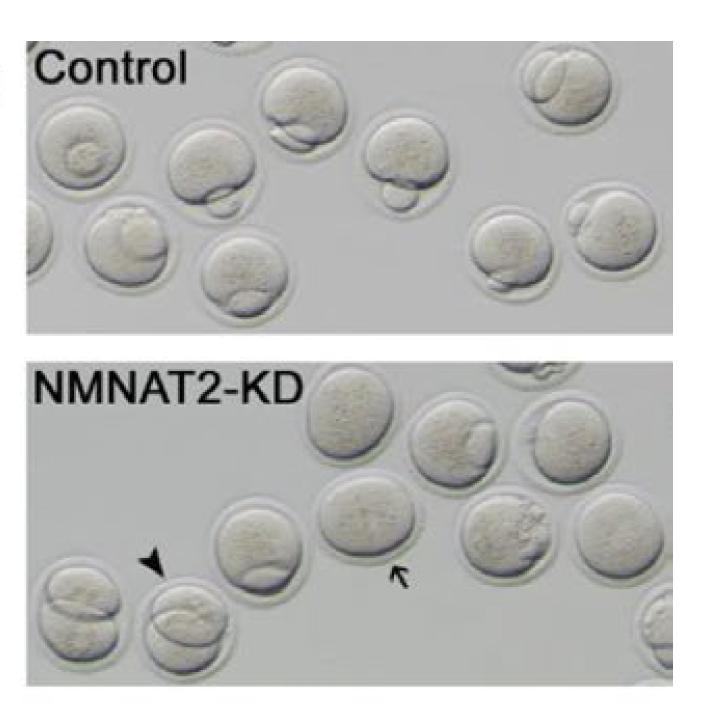

The research team discovered that the drop of NAD+ level in old oocytes was due to the decrease in NMNAT2, an enzyme involved in the process of NAD+ biosynthesis. Oocytes without NMNAT2 have 60 percent less NAD+ content compared to healthy ones. NMNAT2 insufficiency also leads to metabolic dysfunction and defects in egg maturation, in which the oocyte can’t successfully go through cell division or has an abnormal amount of genetic material.

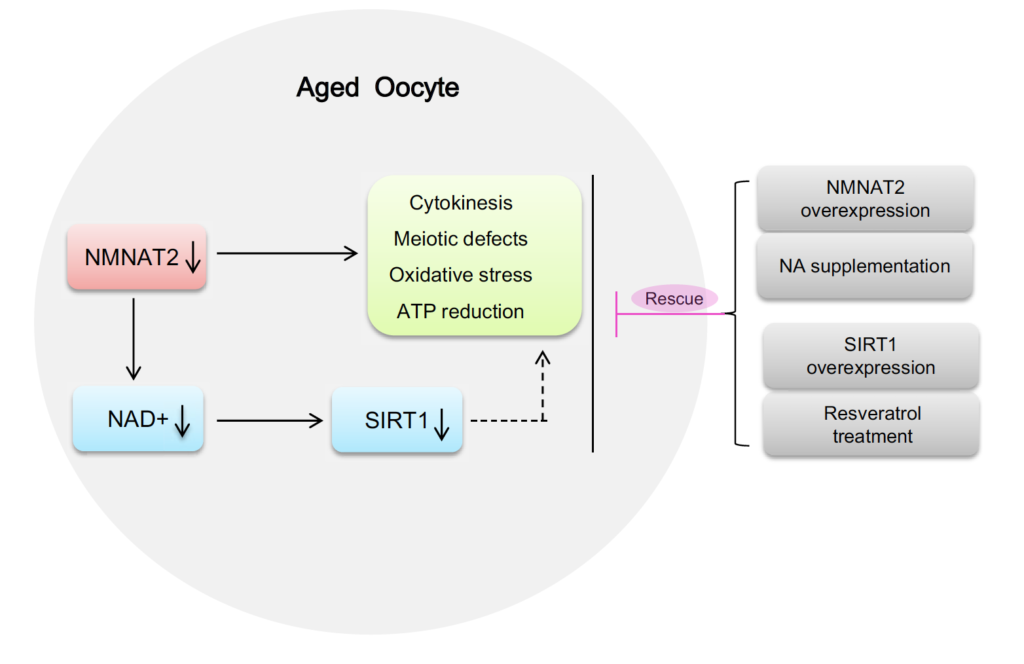

However, replenishing NMNAT2 itself, boosting NAD+ level with nicotinic acid, or activating NMNAT2’s downstream molecule, SIRT1, can improve the quality of aging oocytes. All three methods increased NAD+ levels in the aged oocyte, diminished the defects in egg maturation, and lowered the levels of reactive oxygen species, which are molecules that can damage the tissue.

Diagram illustrating the proposed pathway mediating the effects of NAD+ generation on the quality control of aged oocytes. Loss of NAD+ content and NMNAT2 protein results in the meiotic abnormalities and metabolic dysfunction in oocytes from old mouse. NA supplement and SIRT1 overexpression/activation could partly rescue the defective phenotype of these aged oocytes. (Wu et al., 2019)

“Altogether, based on these findings, we conclude that NMNAT2‐mediated NAD+ generation is essential for quality control of aged oocytes,” stated the researchers in the study.

In 2018, more women in their 30s were having babies than those 20-somethings for the first time, according to a 2019 CDC report. Many women wait to have children for their career and financial reasons. However, a woman’s ability to have a baby begins to decline “gradually but significantly around age 32,” according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

While some women may consider freezing their young and healthy eggs to ensure the chance of holding their baby in the future, the authors of the study say their research may open a new door for female fertility. “Our study indicates a novel mechanism controlling oocyte development of aged mice, which opens a new area for assessing oocyte quality as well as clinical management of fertility issue,” stated the authors.