Eat Less and Live a Long Healthy Life? It Depends on Your Gene

A healthy diet doesn't guarantee a long and healthy life. By tracking over 50,000 flies, researchers found that an individual's genes play a crucial role in determining the effects of diet.

Dietary restriction in decreasing calorie intake and intermittent diet has shown to add extra years and health to animals’ lives. Many research holds the assumption that dietary restriction can slow aging and extend both lifespan and healthspan, the quantity and quality of life together. A study published in Current Biology analyzed genetically distinct strains of fruit flies and found that might not be the case — lifespan and healthspan are not linked under dietary restriction.

Lifespan and Healthspan Linked?

The researchers from the Buck Institute tracked nutrient-dependent changes in lifespan and age-related decline in climbing abilities in more than 50,000 Drosophila melanogaster, fruit flies. As fruit flies age, they climb slower from the bottom of the vial to the top. Researchers measured the flies’ physical performance as an indicator of healthspan.

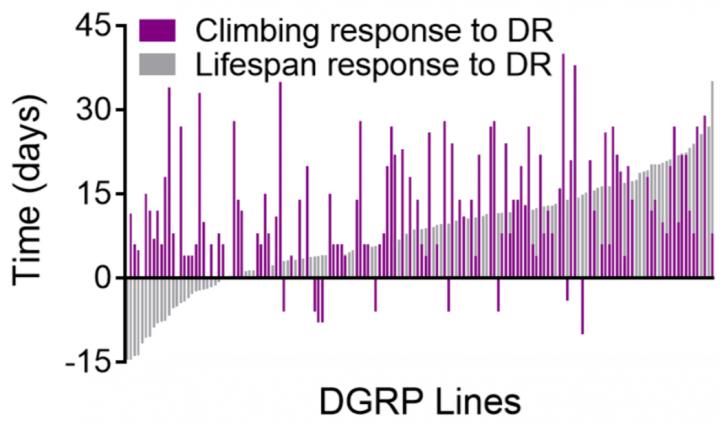

In response to dietary restriction, 97 percent of strains showed some lifespan or healthspan extension, but only 50 percent showed a positive response to both. Fourteen percent showed either a reduced healthspan and increased lifespan or vice versa. Some were more active, but died sooner, while the others lived longer, yet spent more time in poor health. The remaining 36 percent showed no change in either or both lifespan and healthspan under dietary restriction. Although on average, dietary restriction extended lifespan and increased healthspan, individuals respond to the diet differently.

*DR stands for Dietary Restriction, *DGRP stands for Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel. Each of the analyzed fly strains arranged by response to dietary restriction. The overlapping bars show the increase or decrease in lifespan (grey bars) or healthspan (purple bars) when that fly strain underwent dietary restriction. Most strains show positive responses, but a number of strains show negative responses (e.g., the grey bars on the left of the graph lived shorter under dietary restriction). Credit: Kenneth Wilson, PhD

“Dietary restriction works, but may not be the panacea for those wanting to extend healthspan, delay age-related diseases, and extend lifespan,” said senior author Pankaj Kapahi of Buck Institute in a statement. “Our study is surprising and gives a glimpse into what’s likely going to happen in humans, because we’re all different and will likely respond differently to the effects of dietary restriction. Furthermore, our results question the idea that lifespan extension will always be accompanied by improvement of healthspan.”

The team performed a genome-wide analysis to determine the genes that influenced lifespan and age-related physical activity decline in a diet-dependent manner. They identified a gene that alters lifespan “decima,” named after the Roman goddess of fate who used threads to measure one’s length of life. Inhibiting the gene did not improve the climbing ability of flies, but extended their lifespan through reducing the production of insulin-like peptides, short chains of amino acids.

“It’s hard to ask and get relevant results in individuals,” said first author Kenneth Wilson of Buck Institute in the same statement. “With this method, we can ask questions in a much more robust manner and get answers at the population level.”

Wilson and his colleagues also named another gene that influenced the age-related decline in climbing ability, “daedalus,” after the mythological Greek inventor, Daedalus, who crafted wings to escape prison with his son, Icarus. Under dietary restrictions, inhibiting daedalus significantly increased the age-related climbing ability, but only plays a minor role in lifespan.

Besides measuring climbing ability to track physical health in the flies, “other traits associated with healthspan are also important to measure. We need to understand the genetics of age-related decline in other functions, such as vision and cognition,” said Kapahi. “One lesson we have learned is that lifespan extension should not be the gold standard for determining the best means of dealing with age-associated maladies.”

“The majority of people are much more interested in being healthy for as long as possible,” he said. “I think most people, if given the choice, would choose an intervention that would give them extra years of good health over extra years of disability.”

“The fountain of youth” discoveries that extend lifespan in the biology field tends to land in the spotlight as a cure for age-related disease. Kapahi noted that as new “anti-aging” targets emerge, people should be aware that their genetic background will likely have a major impact on how one may respond to an intervention.