Anti-Aging Supplement Rapamycin Slows Muscle and Bone Aging in First Long-Term Clinical Trial

Rapamycin supplementation improves older adults' muscle and bone health in the landmark Participatory Evaluation of Aging with Rapamycin for Longevity (PEARL) trial.

Highlights:

- Supplementing with rapamycin does not lead to serious adverse side effects in older adults.

- Rapamycin improves muscle mass in women and bone mass in men.

Rapamycin — an FDA-approved drug that inhibits mTOR — has proved to be one of the most potent longevity molecules to date, at least for animals. Now, scientists have conducted the first long-term human clinical trial assessing the anti-aging effects of rapamycin on 50- to 85-year-olds as part of the PEARL study.

The PEARL study participants were divided into three groups, each receiving one of the following for 48 weeks:

- 5 mg of rapamycin per week (40 participants)

- 10 mg of rapamycin per week (36 participants)

- 1 placebo pill per week (39 participants)

Rapamycin treatment led to no severe side effects while the 10 mg dose prevented muscle loss in women and bone loss in men, suggesting it can slow some aspects of aging.

Rapamycin Is Mostly Safe

The most common adverse effects reported in the rapamycin groups were gastrointestinal issues. Mouth sores, which are often associated with rapamycin, were reported in the high-dose (10 mg) group but, surprisingly, also in the placebo group. High-dose rapamycin participants also reported altered spatial orientation while the low-dose (5 mg) group reported malaise. None of these side effects are considered severe.

Not all participants were completely healthy, as individuals with well-managed chronic diseases were included in the study. As such, the rapamycin groups reported more frequent chronic issue flare-ups but also reported reduced chronic issue severity compared to the placebo group. Notably, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and the infection rate was slightly lower in the rapamycin groups (15 out of 76, or 19.7 % of participants) compared to the placebo group (10 out of 39, or 25.6% of participants).

“No significant safety-related issues were detected in the blood work results of any participants during periodic check-ins… no significant differences in markers of metabolic health, liver, and kidney function, or moderate to severe adverse events in the rapamycin treatment groups were reported compared to placebo after 48 weeks,” said the authors.

Rapamycin Slows Muscle and Bone Aging

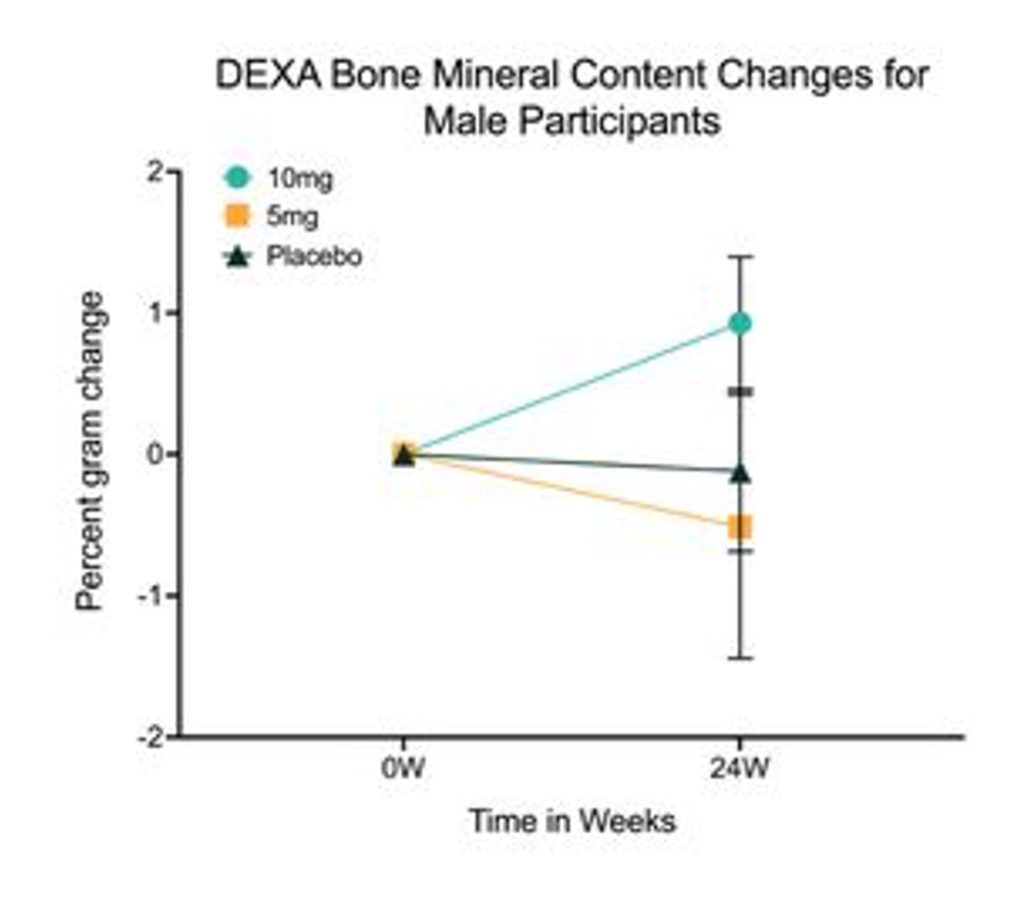

As we age, our bones become porous and hollow, potentially leading to osteoporosis — age-related bone loss. The researchers found that, compared to the placebo group, men in the high-dose rapamycin group had improved bone mineral content. These findings suggest that rapamycin could mitigate bone aging. However, as can be seen from the graph below, there was a high level of variability (vertical bars).

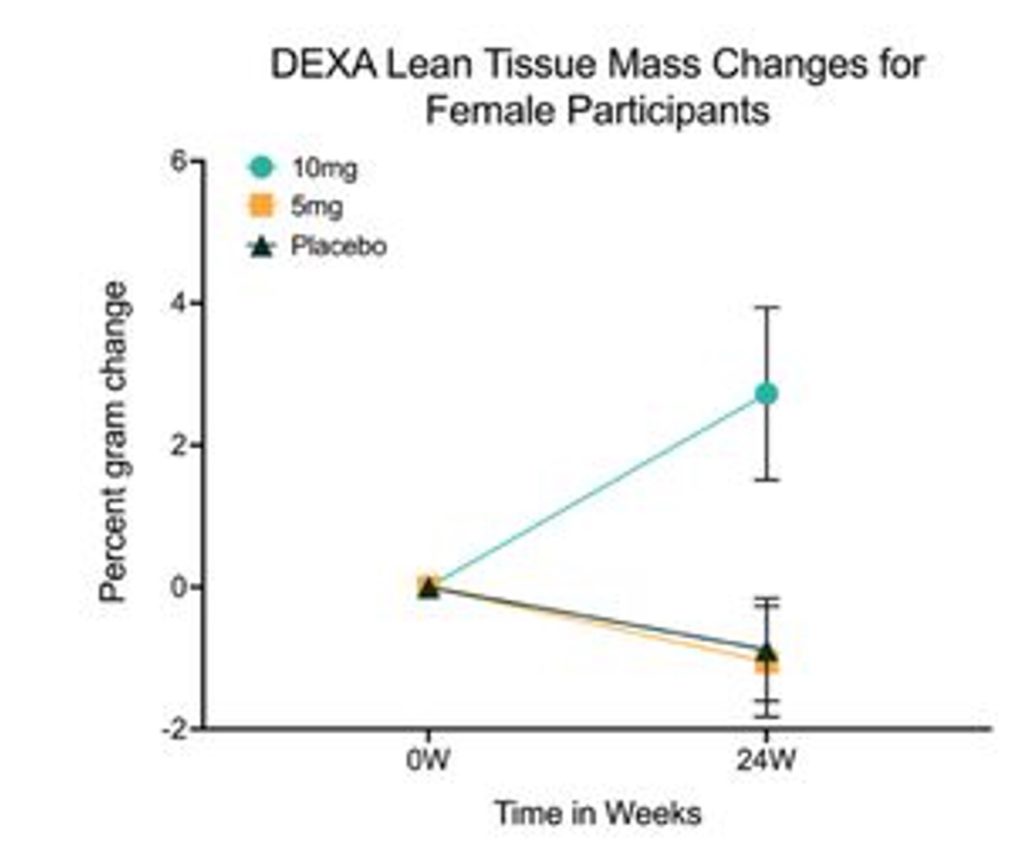

Along with bone loss, our muscles lose mass and strength with age, potentially leading to sarcopenia — age-related muscle loss. The researchers found that, compared to the placebo group, women in the high-dose rapamycin group had improved lean mass, which consists of muscle. The authors estimate that these women gained an average of about 0.5 pounds of lean mass per month. These women also reported improvements in pain, quality of life, and social functioning.

(Harinath et al., 2024) Rapamycin Mitigates Muscle Loss in Women. Compared to the placebo group (black) and the 5 mg rapamycin group (yellow), females in the 10 mg rapamycin group (green) had significantly more lean tissue mass, as measured by DEXA.

Overall, these results suggest that rapamycin may potentially be more beneficial to women than men. However, considering that resistance exercise mitigates both muscle and bone loss, it could be that the participants that benefited the most from rapamycin were the ones who did not regularly exercise. Further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of rapamycin vs resistance exercise on muscle and bone health in older adults.

Expert Opinion: “This Is Really a Safety Trial”

Matt Kaeberlein, PhD, is a longevity expert and host of The Optispan Podcast with Matt Kaeberlein. In a recent video, he gave his expert opinion and commentary on the PEARL study.

He pointed out that the PEARL study was funded by AgelessRx, a for-profit company that sells rapamycin. Therefore, there is a conflict of interest for some of the researchers who conducted the study.

Importantly, Dr. Kaeberlein says that the study was not powered for efficacy and that “this is really a safety trial.” He says this because there were only 115 participants, which is not enough to determine whether rapamycin is the reason for producing an outcome (e.g. improved bone mineral content) without being a result of chance. As such, the muscle and bone measurement results should be taken with a grain of salt.

Dr. Kaeberlein also emphasizes that compounded rapamycin was used in the PEARL study. The bioavailability of compounded rapamycin is about 25% that of commercially available rapamycin (i.e., sirolimus), probably because it does not come in capsules and is partially destroyed in stomach acid. The authors of the study say,

“Compounded rapamycin is approximately 3.5x less bioavailable than commercially available formulations, suggesting that the 5 mg and 10 mg rapamycin groups received an average equivalent of 1.4 mg and 2.9 mg respectively.”

With this in mind, those wishing to try rapamycin as an anti-aging agent should be cautious of the dose if not taking a compounded version. Still, overall, the results of the PEARL study suggest that more research is needed to determine the anti-aging effects of rapamycin in humans.