Understanding Malnutrition in the Elders: Aging and Diet Leads to Molecular Changes in the Intestinal Lining

Aging affects specific regions in our small intestine, and it provides a glimpse to why elders have a harder time adapting to new diets.

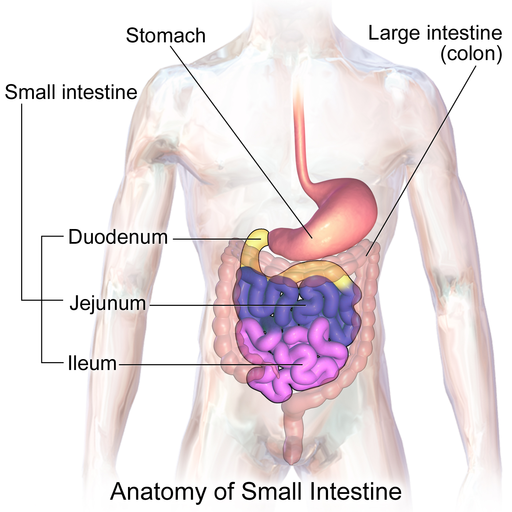

The small intestine, a 20-foot-long coiled tube-like organ, has the important job of absorbing nutrients from what we eat and drink. As we age, the organ loses its structure and functionality, which may lead to malnutrition. Now, scientists discovered that molecular changes in the intestine’s linings caused by aging and diet are one of the reasons. The study appeared in Cell Reports and is the first to investigate the region-specific effects of aging on the intestinal linings.

Aging Reduces Intestinal Stem Cell Activity

The small intestine not only absorbs nutrients through absorptive cells, but it also functions as a barrier against harmful substances by secreting mucus through secretory cells. Deep in the lining of the intestine lies the organ’s secret to multitasking and self regeneration — intestinal stem cells. These stem cells, lodged in a pocket of tissue called crypts, generate cells to repopulate the linings every three to five days throughout our lives. But in an aging intestine, stem cells lose their ability to maintain that balance, which disrupts the integrity of the intestinal lining.

Analyzing the protein expression of crypts across 12 different sections of the small intestine in mice, the research team characterized the spatial variation along the organ’s cells. In young mice, the researchers discovered a high number of specialized mucus-secreting cells called goblet cells tucked in the ileum, the small intestine’s final and longest segment. However, in aged mice, the number of goblet cells decreased and the effect of aging on the crypt is similar to that of bacterial infection — an increased level of proteins related to immune response and reduced stem cell activity.

“Our results show a clear effect of aging on the set of proteins and cellular composition of intestinal crypts,” says first author Nadja Gebert of Fritz Lipmann Institute in an interview published on Medical Xpress. “We found some major changes in inflammation-related proteins and decreased levels of stem cell markers. This shows that the delicate structure of the epithelium gets disturbed during aging, which leads to inflammation and reduced self-regeneration.”

The research team also found that the aged intestine has a reduced ability to adapt to dietary changes. The team refed the mice after putting them on a dietary restriction similar to intermittent fasting, a diet which has shown a lifespan-extending property across species. The diet change affected an abundance of proteins in young animals. In contrast, the old animals responded poorly to the change with fewer modified proteins and took longer to regain weight after refeeding.

However, the fasted-and-fed-diet restored the goblet cells in the intestinal crypts of old mice, suggesting a potential anti-aging effect through dietary intervention. Taking a closer look, the team identified a modulator of stem cell differentiation that responds to dietary changes — enzyme Hmgcs2. Refeeding mice that underwent dietary restriction rapidly reduced Hmgcs2 levels in intestinal stem cells and signaled the cells to differentiate into mucus-secreting cells like goblet cells.

“It is tempting to speculate that these effects might contribute, at least in part, to the health-promoting effects of dietary interventions based on intermittent fasting,” wrote the authors of the study. “However, further investigations are required to demonstrate a causal link between this type of intervention and improvement of intestinal functions.”

Also known as the “hidden epidemic in older adults,” malnutrition contributes to a progressive decline in health, reduced physical and cognitive functions. Alarmingly, the estimated health care costs of disease-associated malnutrition in the U.S. for older adults is $51.3 billion. The study provides scientists insights on how to restore the regenerative capacity of old intestines for the elders to maintain a healthy life.